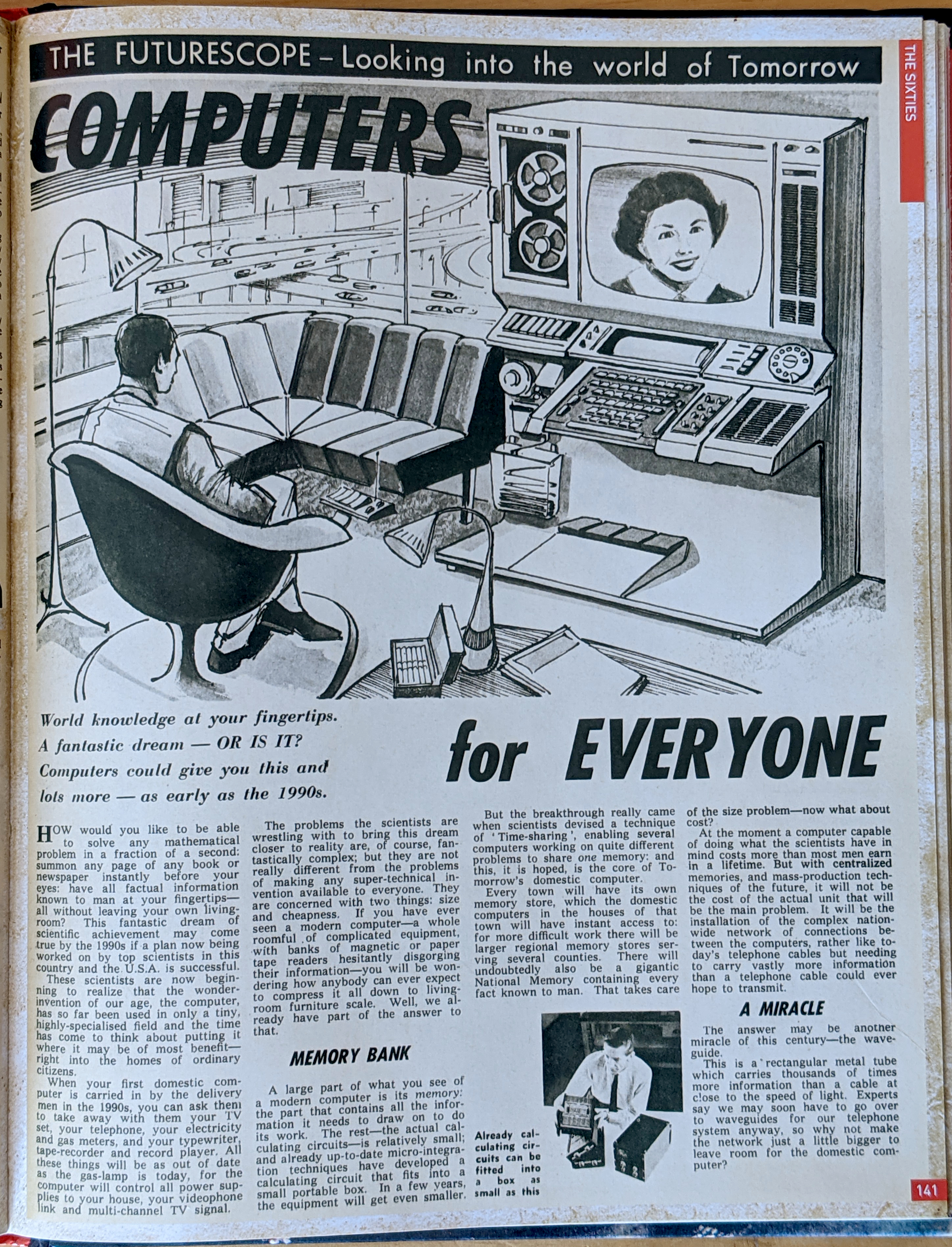

The Futurescope — Looking into the world of Tomorrow

I have long been a fan of Futurology, a term that to me encompasses the collection and examination of writings, mixed-media, and other works of art that depict how life will be in the future. The title of this post (The Futurescope….), as well as the rest of the text below the image, is a word-for-word reproduction of a piece that appeared in a 1965 Eagle comic. Eagle was a popular young adult comic series that ran in the UK from 1950 to 1969 and is fascinating in its own right. You can read more about it on the Wiki site. I came across this gem in the Eagle Annual: The Best of the 1960s Comic, an anthology of the magazine’s stories and articles for the entire decade.

I am amazed by its prescienc, with how it anticipated that computers would come to dominate our daily lives, as well as the timeline it offered, the 1990s. There is much it got wrong but considering this was published just as ARPANET, precursor to today’s Internet, was becoming a thing, it is astounding.

I hope you have as much pleasure reading it as I did.

COMPUTERS for EVERYONE

World knowledge at your fingertips.

A fantastic dream — OR IS IT?

Computers could give you this and

lots more — as early as the 1990s.

HOW would you like to be able to solve any mathematical problem in a fraction of a second: summon any page of any book or newspaper instantly before your eyes: have all factual information known to man at your fingertips—all without leaving your own living room? This fantastic dream of scientific achievement may come true by the 1990s if a plan now being worked on by top scientists in this country and the U.S.A. is successful.

These scientists are now beginning to realize that the wonder-invention of our age, the computer, has so far been used in only a tiny, highly-specialized field and the time has come to think about putting it where it may be of most benefit—right into the homes of ordinary citizens.

When your first domestic computer is carried in by the delivery man in the 1990s, you can ask them to take away with them your TV set, your telephone, your electricity and gas meters, and your typewriter, tape-recorder and record player. All these things will be as out of date as the gas-lamp is today, for the computer will control all power supplies to your house, your videophone link and multi-channel TV signal.

The problems the scientists are wrestling with to bring this dream closer to reality are, of course, fantastically complex; but they are not really different from the problems of making any super-technical invention available to everyone. They are concerned with two things: size and cheapness. If you have ever seen a modern computer—a whole roomful of complicated equipment, with banks of magnetic or paper tape readers hesitantly disgorging their information—you will be wondering how anybody can ever compress it all down to living room furniture scale. Well, we already have part of the answer to that.

MEMORY BANK

A large part of what you see of a modern computer is its memory: the part that contains all the information it needs to draw on to do its work. The rest—the actual calculating circuits—is relatively small; and already up-to-date micro-integration techniques have developed a calculating circuit that fits into a small portable box. In a few years, the equipment will get even smaller.

But the breakthrough really came when scientists devised a technique of ‘Time-sharing’, enabling several computers working on quite different problems to share one memory: and this, it is hoped, is the core of Tomorrow’s domestic computer.

Every town will have its own memory store, which the domestic computers in the houses of that town will have instant access to: for more difficult work there will be larger regional memory stores serving several counties. There will undoubtedly also be a gigantic National Memory containing every fact known to man. That takes care of the size problem—now what about cost?

At the moment a computer capable of doing what the scientists have in mind costs more than most men earn in a lifetime. But with centralized memories, and mass-production techniques of the future, it will not be the cost of the actual unit that will be the main problem. It will be the installation of the complex nation-wide network of connections between the computers, rather like today’s telephone cables but needing to carry vastly more information than a telephone cable could hope to transmit.

A MIRACLE

The answer may be another miracle of this century—the waveguide.

This is a rectangular metal tube which carries thousands of times more information than a cable at close to the speed of light. Experts say we may soon have to go over the waveguides for our telephone system anyway, so why not make the network just a little bigger to leave room for the domestic computer?

Recent Comments