The Boy Who Rode His Pony 1,600 Miles To Meet The President

One day in late spring of 1928, fourteen-year-old high school sophomore Boyd Manson Jones decided he was going to ride his horse from his home outside Gallup, New Mexico, all the way to Washington, D.C., where he would extend a personal invitation to President Coolidge to attend that year’s Inter-Tribal Indian Ceremonial, then in its seventh year. The precise reasons behind his decision are lost to history but it is believed that his intent to promote tourism in his hometown had a lot to do with helping his family’s own personal finances.

The Intertribal Indian Ceremonial began in 1922, the brainchild of Mike Kirk, of the Kirk Brothers trading post empire. Mike owned a trading post in Manuelito, New Mexico and had spent years immersed in Indian culture and jewelry making. The Kirk Brothers owned many of the trading posts within the Navajo, Hopi, and Zuni territories at that time. They also operated a large wholesaling post in Gallup that sold almost exclusively to other trading posts throughout the region. In addition to running his trading post, Mike Kirk promoted various events throughout New Mexico and the southwest. He formed a traveling road show, featuring Indian dancers, artisans, and storytellers.

![Mike Kirk's Trading Post in Manuelito, NM - 1935 [Burton Frasher Sr. 1888-1955, Pomona Public Library/Frasher Foto Postcard Collection]](http://www.davidgunter.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/mike_kirk_trading_post-1935.jpg)

In 1922 Kirk hit upon the idea of a multi-day festival that would mimic the yearly caravans of tribal families that would head into Gallup for reunions. He sought a way for the Indians to come together to celebrate as well as for them to showcase their culture, arts, and crafts to non-natives willing to make the trip eastward on the outskirts of town. Gallup’s growing reputation as the unofficial capital of Indian country all but ensured they would come. With the backing of the local Kiwanis they scheduled the event over three days at the end of September. That first year it consisted of campfire dances, a “game of base-ball”, a tug-of-war, and a relay marathon. The participating communities consisted of the Navajo and Hopi nations, and the Pueblos of Zuni, Taos, Jemez, Isleta, Acoma, and Laguna. Fox Films came out to capture silent film footage of the event.

In its early years, the Ceremonial Association struggled from one year to the next to raise enough money to put on the celebration. Then in 1927 word arrived in Gallup that the city of Albuquerque was planning to host its own Indian ceremonial and at around the same time of year as Gallup’s. The fears proved to be unfounded when Albuquerque community planners wired back word that the festival they planned would highlight more than just native culture. Theirs would feature Spanish and cowboy culture in addition; and it would be held more than a month later, at the end of September (the Gallup ceremonial had moved to August by then, to allow time for students to attend).

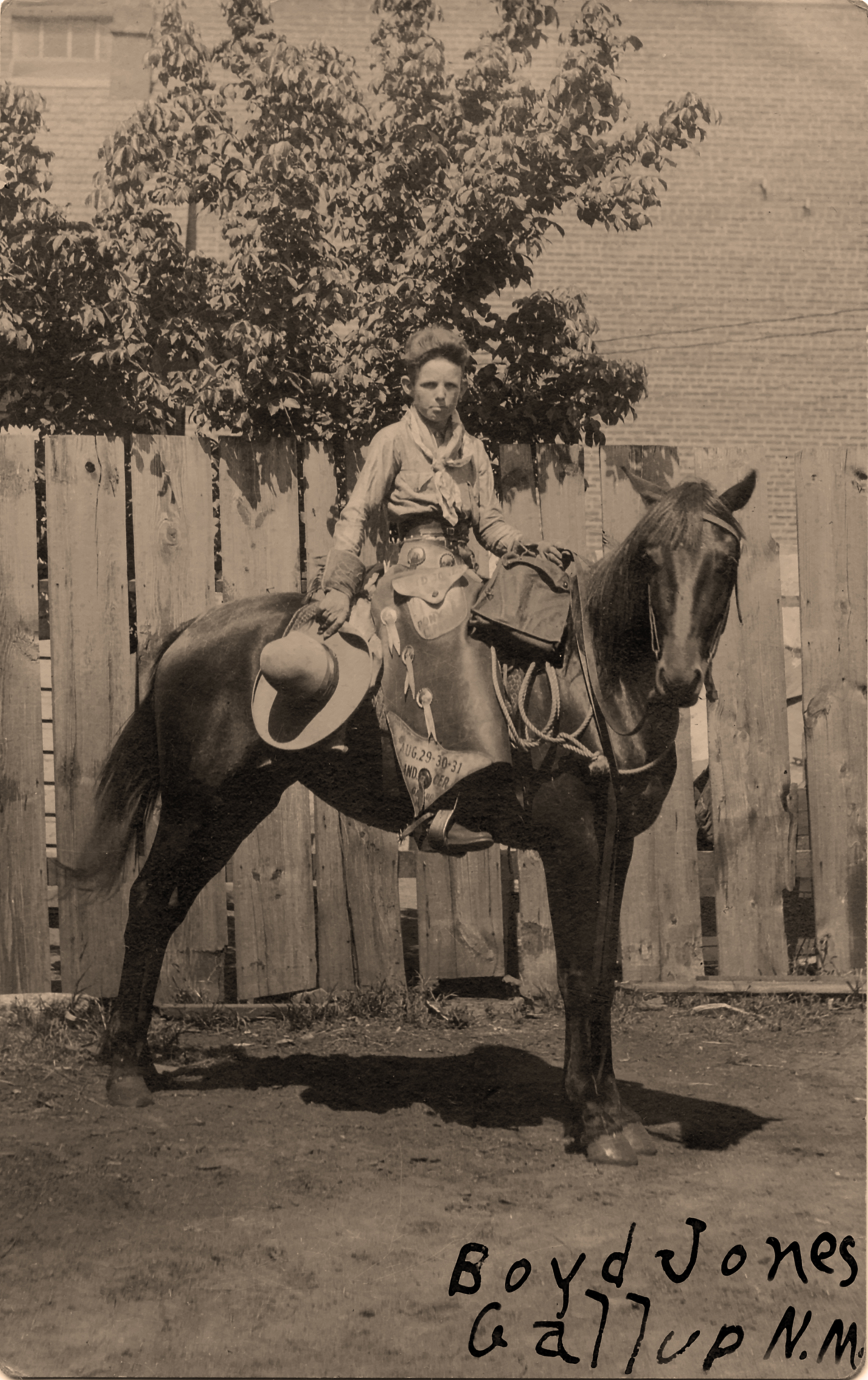

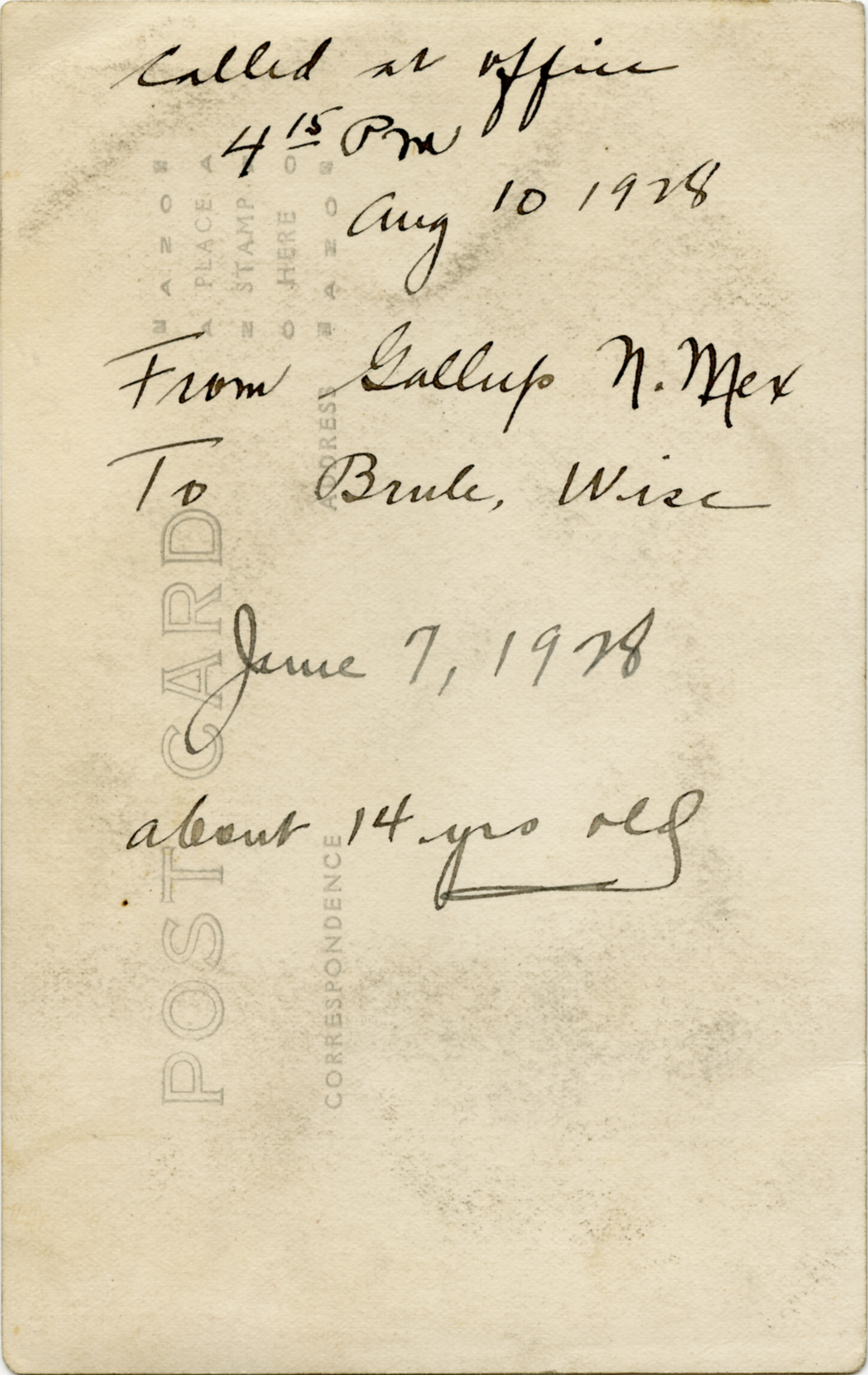

Nevertheless, keeping the fledgling Ceremonial going was the topic of conversation among many civic-minded people in Gallup and this included Boyd Jones’ parents, James Manson and Eunice Amber (Jenkins) Jones. The Jones, originally from Texas, married in 1906 and settled immediately in Gallup, where James had begun working as a fireman for the Santa Fe Railroad. He retired from that position a decade later when the family homesteaded a region just south of Gallup, today known as Bread Springs. In addition to running their small ranch, they owned a trading post and generally benefited from the influx of tourists and out-of-state tribal members attending the multi-day celebration. By then it had grown to include many eastern and northern tribes and even one from Mexico. The idea for the trip came from Boyd’s father, then recuperating in an Oklahoma hospital from some unknown but none-too-serious illness. Boyd Jones attended high school in his parents native Amarillo, Texas, where his grandparents lived. Having returned to Gallup for the summer and faced with the prospect that his father would be laid up for a spell, he was up for an adventure. Once back in Gallup, Boyd discussed matters with a local reporter named Y. Powers and with the Ceremonial Association. Surprisingly, everyone was enthusiastic and supportive of the idea. The Association decided that Boyd could hand out tickets to the event to newspaper editors, officials and politicians of note that he would encounter along the way. Boyd, clad in his fanciest cowboy clothes and astride his faithful mare—a five-year-old Cayuse Indian pony named Molly—posed for a photograph and then printed up a few dozen postcards to hand out along his journey. The Ceremonial Association also gave Boyd $50 for expenses. Thus, some time after June 7th (the date the photo was taken), Boyd Jones and Molly set off on what would become a 1,600 mile trip to see President Coolidge.

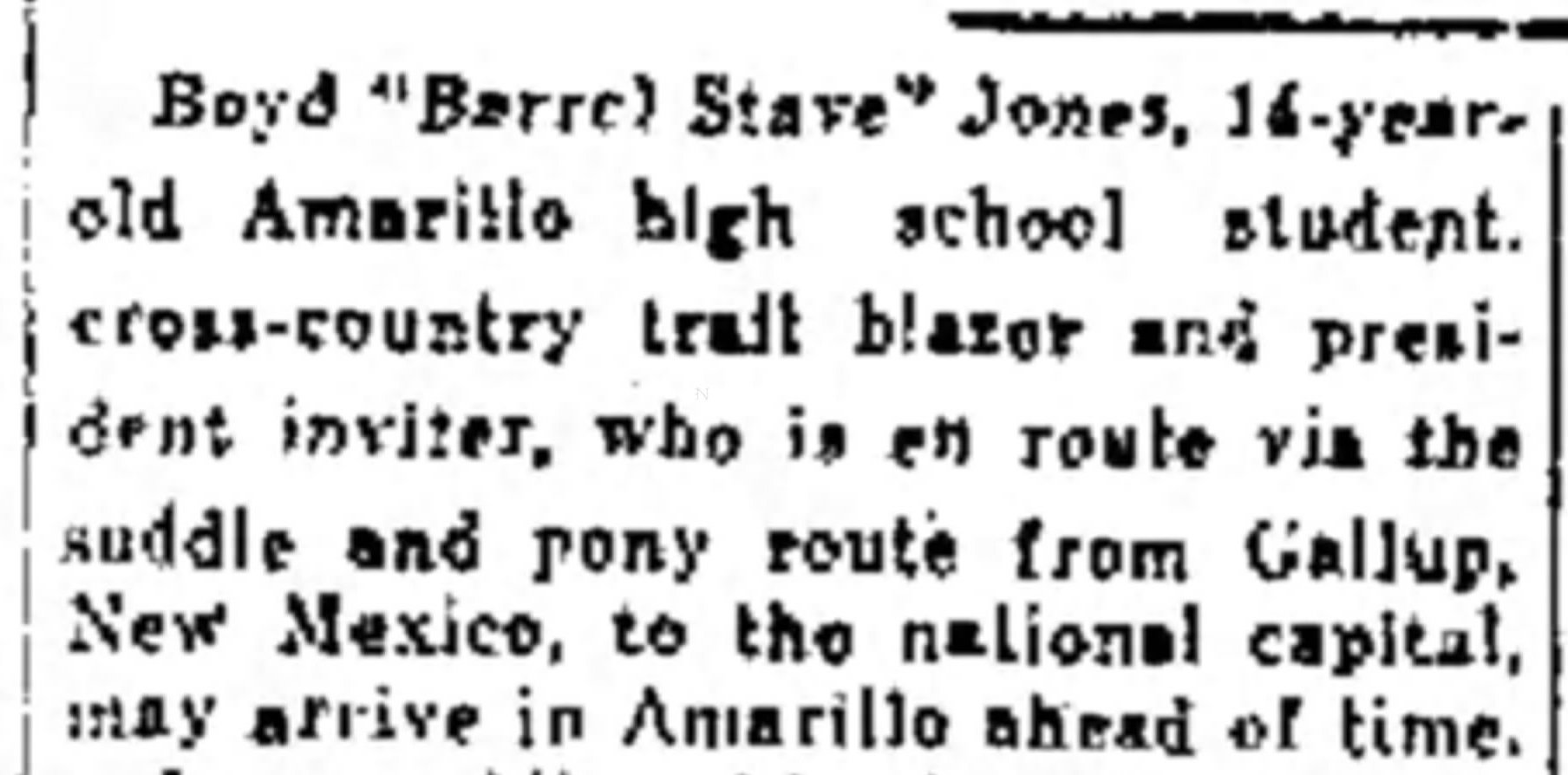

He reached Albuquerque a few days later, around 10 June. He met up with staff from the Associated Press who let the boy know that President Coolidge had already left the White House for his summer vacation home in Brule, Wisconsin, on the edge of Lake Superior. Boyd had to decide whether he wanted to stick with the original plan to head to Washington, D.C. or head on to Wisconsin. He had time. The Associated Press had decided to publish the exploits of the young lad’s trip, a major story that went on to appear in newspapers throughout the country all summer long. On 12 June he took a side trip by bus up to Santa Fe where he spent the evening in the company of Governor Richard Dillon and other local dignitaries. He returned to Albuquerque the next day with an official letter of invitation from Gov. Dillon to President Coolidge, and messages to deliver to other governors and mayors along his route. He left Albuquerque the next morning, 14 June 1928, laden with his pack, satchel of letters, postcards, and clad in his 10-gallon Stetson hat, leather chaps, pink silk shirt, and shiny spurs. The only hold-up he anticipated along his journey would happen when he reached Amarillo, Texas. You see, his mother had been in Amarillo before Boyd had left home from Gallup, visiting her parents. She had not been told of the trip. Boyd said at the time he left Albuquerque, “I will be in Amarillo next Sunday and if my mother doesn’t stop me with a barrel stave I’ll be lucky.” That earned him the nickname that newspapers would use for the following weeks.

We don’t have a record of what actually did happen when he reached Amarillo, but his journey didn’t end there. Averaging about 29 miles per day, he next passed through Santa Rosa and Clovis, New Mexico and landed in Amarillo on 23 June. He visited a few days with his mother and grandparents before heading out for Oklahoma City and on into Tulsa. From there he made the decision to turn northward, to Joplin and towards Wisconsin. He reckoned that he would make Brule in sufficient time before President Coolidge returned to the White House.

He arrived in Des Moines, Iowa, 31 July and made another press appearance, posing for another photo. By then he was averaging 30 miles per day, still, and resting on Sundays. He had spent the $50 the Ceremonial Association gave him for the trip and they wrote to him that he should turn back. Instead, he raised money with his press appearances, selling the postcards he brought along with him. The Association eventually wired him another $50 to complete his trip. Boyd mentioned to reporters that the further north he traveled, the harder it was to find lodging for Molly each night. Garages were reluctant to take in a horse and finding stables took some time each evening. This had the effect of sending out a call to locals in towns still left on his route to help aid the process.

From Des Moines he headed up to Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota, arriving on 10 August. He met with Minneapolis Mayor George Leach and extended an invitation to come to Gallup for the Ceremonial. He then traveled over to St. Paul where he called on Governor Theodore Christianson, who was unavailable. He left the postcard that is the subject of this story with staff who wrote on the back,

He had his photo taken on the steps of the state capitol while delivering a message from New Mexico Gov. Dillon, to State Attorney General A. Youngquist.

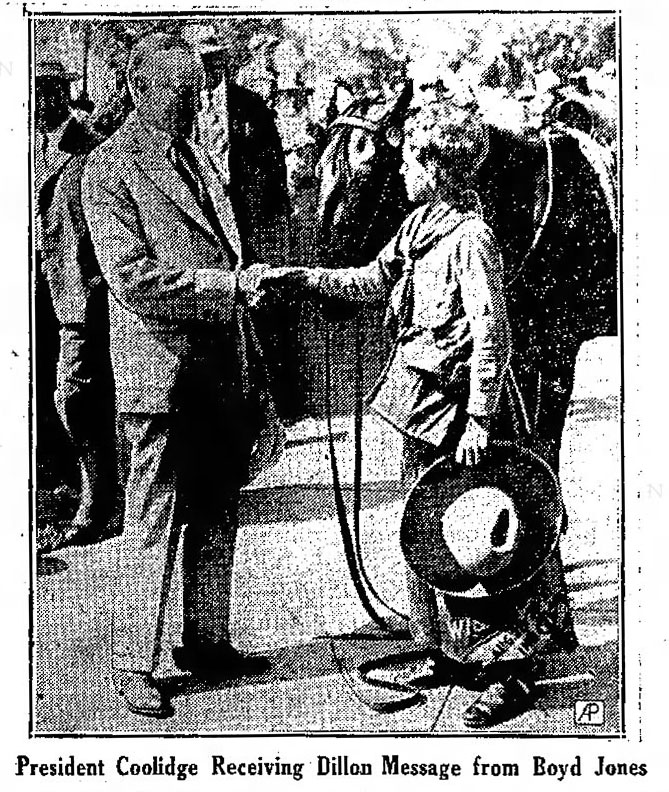

It was on to the final stretch over to Brule over the next seven days. Boyd Jones and his horse Molly arrived on 17 August 1928 and delivered their messages to President Coolidge. The president congratulated the lad on his successful ride and sent wire back to New Mexico thanking the governor for his letter and expressing regrets at not being able to attend the festivities. He wrote,

My dear Governor Dillon:

Master Boyd Jones this morning handed me your letter of June 13th in which you very kindly join with the Inter-Tribal Indian Association of New Mexico in extending to me a cordial invitation to be present at the Inter-Tribal Indian Ceremonial to be given at Gallup, New Mexico, August 29th to 31st. While it is not possible for me to attend the Ceremonial, I hope it will be a thoroughly enjoyable and successful occasion.

I was pleased to meet Master Jones and interested to learn he had made the entire trip from Santa Fe to Superior on horseback. I deeply appreciate not only the invitation itself and your endorsement of it, but this unique way of presenting it to me.

Very truly yours,

Calvin Coolidge.

And with that, Boyd Jones and Molly’s 1,600 mile journey had come to and end.

Boyd’s father awaited him with the family’s Model-T to make the return trip by automobile. There remained one problem: what to do with Molly? That question and the boy’s decision to leave her behind sparked quite a row.

The cost to ship Molly back by train was $160, “more than the mare is worth” in Boyd’s words. He therefore decided to set her loose with a pat on the rear, hoping she would find her own way home. The backlash was swift and condemning. An op-ed piece in the Portland Oregonian wrote:

“Somehow, we don’t like that picture. And so far as we are concerned the bloom is very definitely departed from the adventure. We entertain our doubts as to the feasibility of the mare finding her own way back, or forage as she travels. It is wholly possible that she might fall among thieves or junkmen… You cannot quit a horse like that—if you are a horseman. And the worth of a horse is not the cost of the freight.”

Authorities in Minnesota let the boy know that, at least within that state, it was illegal to abandon an animal in such a manner, and ethically irresponsible elsewhere. A Boy Scout troop in Wisconsin came up with the idea of returning Molly to New Mexico Pony-Express style. They would have chosen riders take her 60 miles at a time from one leg to the next, with participating troops across the many states getting involved. It proved to be untenable, however, when not enough riders could be found, especially in the vast stretches of the west once you leave Missouri.

Wisconsin radio station WEBC broadcast an appeal to raise the $160 but funds could not arrive in time for the Jones, who had to be back for the start of the Ceremonial. The Associated Press came through with around $50 to provide hay and feed for Molly, who was left to pasture with a local farmer until a permanent solution could be arranged. Boyd and his father headed back to Gallup, leaving the controversy behind them.

Molly became the subject of subsequent news stories throughout the winter of 1928 and into the following year. She was attacked by other horses at the farm where she was initially left. A woman in Texas felt that Molly really needed to be back in the southwest and forwarded along a request to purchase her outright and bring her home. She was eventually turned over the care of the Deluth, Minnesota Zoo where curator Bert Onsgard gave her a safer environment and Molly gave rides to children around the zoo grounds. In March of 1929, Eunice Jones had had enough of the news stories and of her son’s disregard for the mare that she wired the money to the zoo, paying for her keep and for her return home. Molly and Boyd were reunited in April of 1929.

The Jones made it to Amarillo in the Model-T and Boyd was put on a train to make the return trip to Gallup, arriving just in time on the eve of the 7th annual Inter-Tribal Indian Ceremonial. Boyd was a featured guest of honor, along with Gov. Dillon and big-time Hollywood actor Richard Dix, in town for having just finished filming one of the early sound films, Redskin, in neighboring Canyon de Chelly (with the backing of the Navajo Nation). Boyd rode in the parade during opening festivities in the town, though on a borrowed horse, of course, and the local press made sure to point that out. The opening day attendance of the Ceremonial broke all previous records many times over. To that end, Boyd’s adventure had been a worthwhile endeavor.

The story would otherwise end here yet the following spring, a then 15-year-old Boyd Jones, once reunited with Molly, decided he needed another adventure. This time he decided to promote a local fair going on in his school town of Amarillo, Texas. He set out in June of 1929, again astride Molly, to travel all the way to Washington, D.C. this time, and personally invite President Herbert Hoover to attend. The 1,800 mile trip pretty much went along as well as the previous trip, with Boyd arriving in August, 1929, and after meeting with the President’s staff, proceeding on to New York City where he rode Molly up and down Broadway and appeared before a few crowds. Once again, the AP covered his antics. The outcome of this second trip had a better outcome for Molly. When Mr. Jones met up with Boyd in New York, he made sure to have a horse trailer in tow. All of them safely returned to Gallup.

Boyd finished high school and continued to work on his parents ranch afterwards. At the start of the US involvement in WWII, he enlisted and served as a sergeant with the 207 Signal Depot in Europe. After the war he remained in Gallup and married a Navajo woman, Bertha Louise Hubbell, from nearby Tohatchi, New Mexico, in 1951. They had two daughters, Ramona and Cheryl. Their marriage lasted a decade before Bertha departed for Los Angeles, California, in 1961. She would go on to marry three more times in her life.

Boyd worked as a cook in a local café until he eventually bought the place. Boyd’s Café opened up in the former soda fountain adjacent to Melton’s Pharmacy at 200 W. Coal in Gallup in 1962. In 1969 he purchased a second café, the long-standing (c1919) Mahattan Café just down the road.

Boyd died unexpectedly of a heart attack on 3 October 1970, leaving behind two adult daughters, his parents, and several brothers and sisters. Cheryl ran the restaurants for a few years but eventually gave up. Today, the building housing Boyd’s Café houses a title loan business. The former Manhattan Café serves as an insurance agency.

Molly passed away a few years after the 1929 trip, after she ate some poisoned hay that had been fouled by a major dust storm. This was according to a 1972 interview with Boyd’s father in the Gallup Independent (9 Aug 1972, p. 33).

Following thirty years of farming, James Manson and Eunice Jones donated their pinto bean farm (“largest in New Mexico in its day”) to found the Jones Ranch School and Mission, established for Navajo children and run by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. It is known today as Chi Chil’Tah (Diné language) or the Jones Ranch Community School. James passed away on 12 Dec 1975 in Gallup, and Eunice three years later on 12 October, 1979.

Epilogue

I keep wondering what really made Boyd Jones dare to take a 1,600 mile trek on horseback, and another 1,800 mile trip a year later. In scouring old newspapers for his story, I came across several instances where in the same paper—on the same page even—stories appeared announcing that some new aviation record or accomplishment had been achieved. Remember, this is one year after Charles Lindbergh’s 1927 solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean. This got me thinking about the decade of the 1920s as a whole.

It was known as the Roaring Twenties, a collective backlash against the previous culture that brought on the likes of The Great War. It was a period of unprecedented economic growth (42% in the US covering the years 1919-1929) which lead to a rise in mass consumerism and leisure time. The rise of jazz music and dynamic dances stemming from it represent the overall shift in culture and the budding radio industry helped spread it around like wildfire.

Perhaps also because of radio and the growing moving picture industry there was an increased fascination with actors and athletes that elevated them to major celebrity status. The biggest names of the decade include actors Greta Garbo, Rudolf Valentino, and Mary Pickford. Non-actors include boxer Jack Dempsey, golfer Bobby Jones, and many baseball players, notably Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, and Lou Gehrig. They were among the first generation of celebrities to be known across the entire country by nearly everyone, as cheap radio sets could be had by even the poorest households and people could see them in newsreels in movie houses popping up at a rapid pace.

The decade of the 1920s also became one of feats of endurance and record breaking attempts. This largely has to do with the rise in automobile production, the rapid growth of the aviation industry, and the increase in leisure time mentioned previously. Auto tourism became a major activity with the opening up of major US highways that allowed people to flow into previously inaccessible areas, away from the rail tracks that had criss-crossed the country in the previous century. Soon people were seeing who could travel the furtherest or the fastest on four wheels. The same goes for aviation. Planes were getting bigger, could fly further and faster than before. It became possible to fly not only across the Atlantic but over portions of the Pacific and down to South America, and so on. Aviation “firsts” were appearing almost monthly in newspapers.

Culturally this was reflected with the invention and spread of popular dance marathons, kissing marathons, pole sitting, and other endurance activities anyone could participate in.

With that as the background, I imagine a lad like Boyd Jones, whose family was upper-middle class and generally informed on goings on in society, could have been easily influenced in his decision to set off on these long treks. It would have seemed the typical thing to do. The surprising bit to me is the general approval and support of this idea by much older adults. Perhaps I’m a bit too far removed from history to understand just what a typical fourteen-year-old was capable of back then.

Recent Comments