Nell “Nellie” Catherine Bunyan Jennings Hardwick

It has been quite some time since I published one of my Postcard Stories. The reason is that I came across a postcard whose author is connected to a convoluted web of interesting characters. Fleshing out their stories has taken longer than I expected.

The tale is quite a whopper. It includes a local newspaper woman from small town Oklahoma on her honeymoon with her second husband; her former husband, an outlaw-turned-lawyer-turned-oilman-turned-Hollywood producer; a famous boxing bout; and the famous writer O. Henry, to mention only a few.

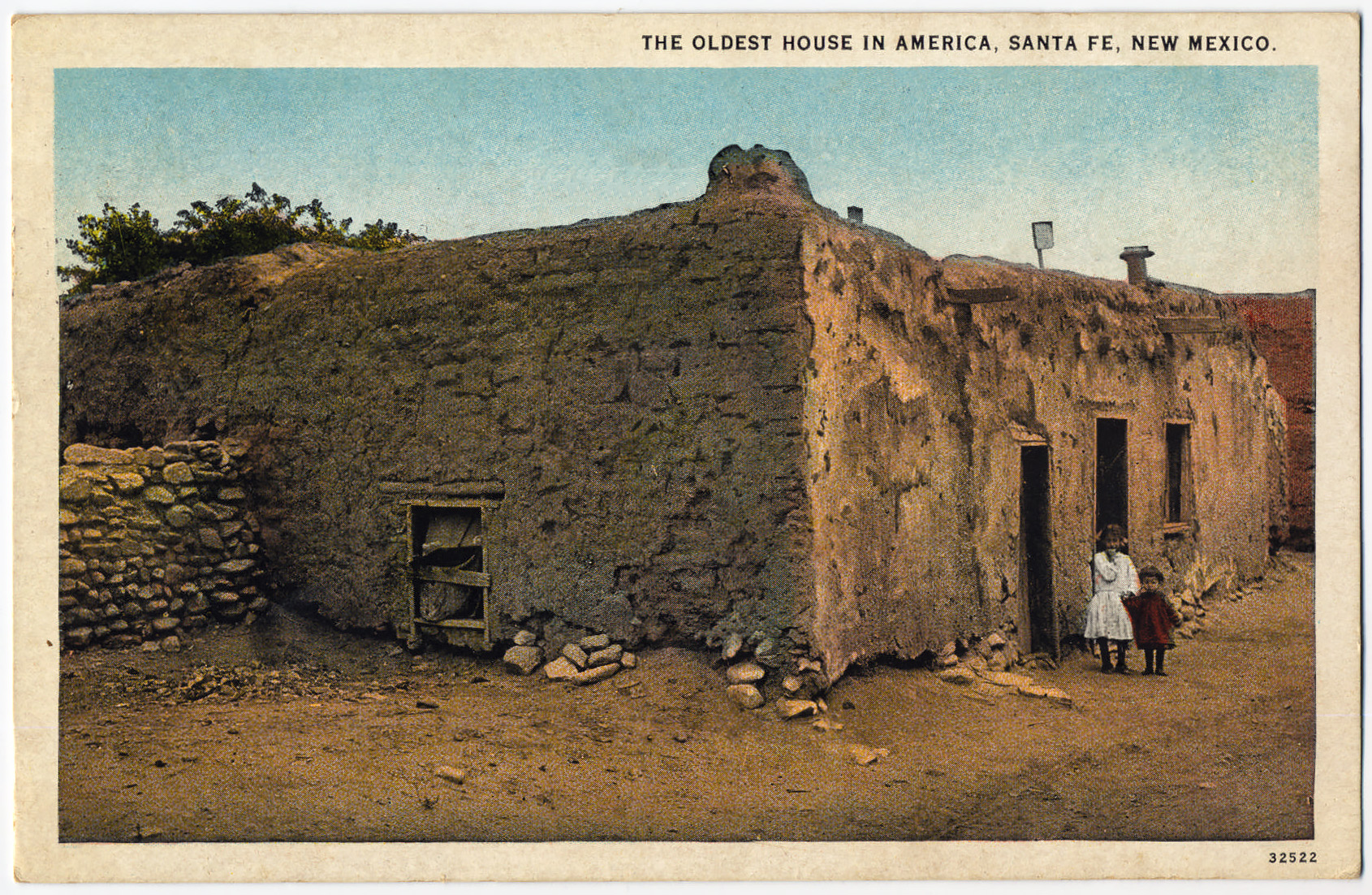

The subject of this 1928 post card is a locally famous scene from Santa Fe, New Mexico. It depicts “the oldest house in America”, a pueblo dwelling repurposed during the Spanish conquest of the region in 1605 and which today serves as a museum.

From the printed text (reverse),

“Santa Fe, the oldest town inhabited by whites in America, was originally an Indian Pueblo. Its earliest historical mention is 1605, when it became the capitol of the province, which proves that it was already a Spanish town. Undoubtedly the first settlement was in the 16th century by Spanish adventurers who settled in the Pueblo much as the later Squaw Men settled among the Indians of the plains. The erection of this house, so tradition relates, was by the Pueblo Indians before the coming of the Spanish settlers.”

The reverse contains the following hand-written message.

“Thurs July 25

Dear Mamma: We stopped here to see the sights & hear the prize fight. Had a lovely day & enjoying ourselves immensely.

Nelle & Lou”

The letter was addressed to Mrs. C. S. Bunyan of Pond Creek, Oklahoma, and postmarked at 8:30AM on 27 July, 1928, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

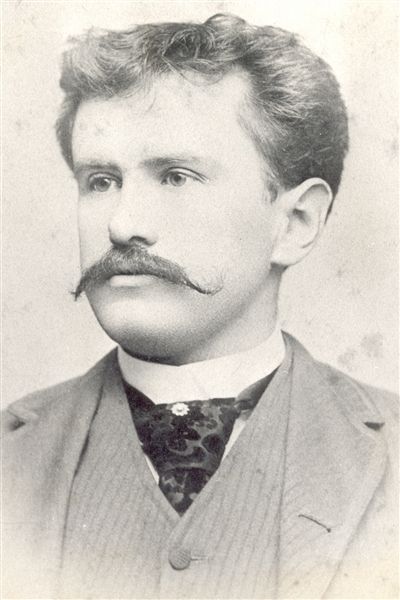

The author of the postcard was Nelle “Nellie” Catherine Bunyan Jennings Hardwick. She was the eldest of seven children born to Charles Sylvester and Mary Ellen “Mollie” Bunyan. When she was born on 23 October 1885, the family was living in Kansas City, Kansas but very soon afterwards they homesteaded in the new Oklahoma territory. They settled eventually in Pond Creek, Oklahoma, where her parents would remain throughout the rest of their lives. C. S. Bunyan went on to become the Marshall of Grant County and the family was well received locally among the higher ranks of society.

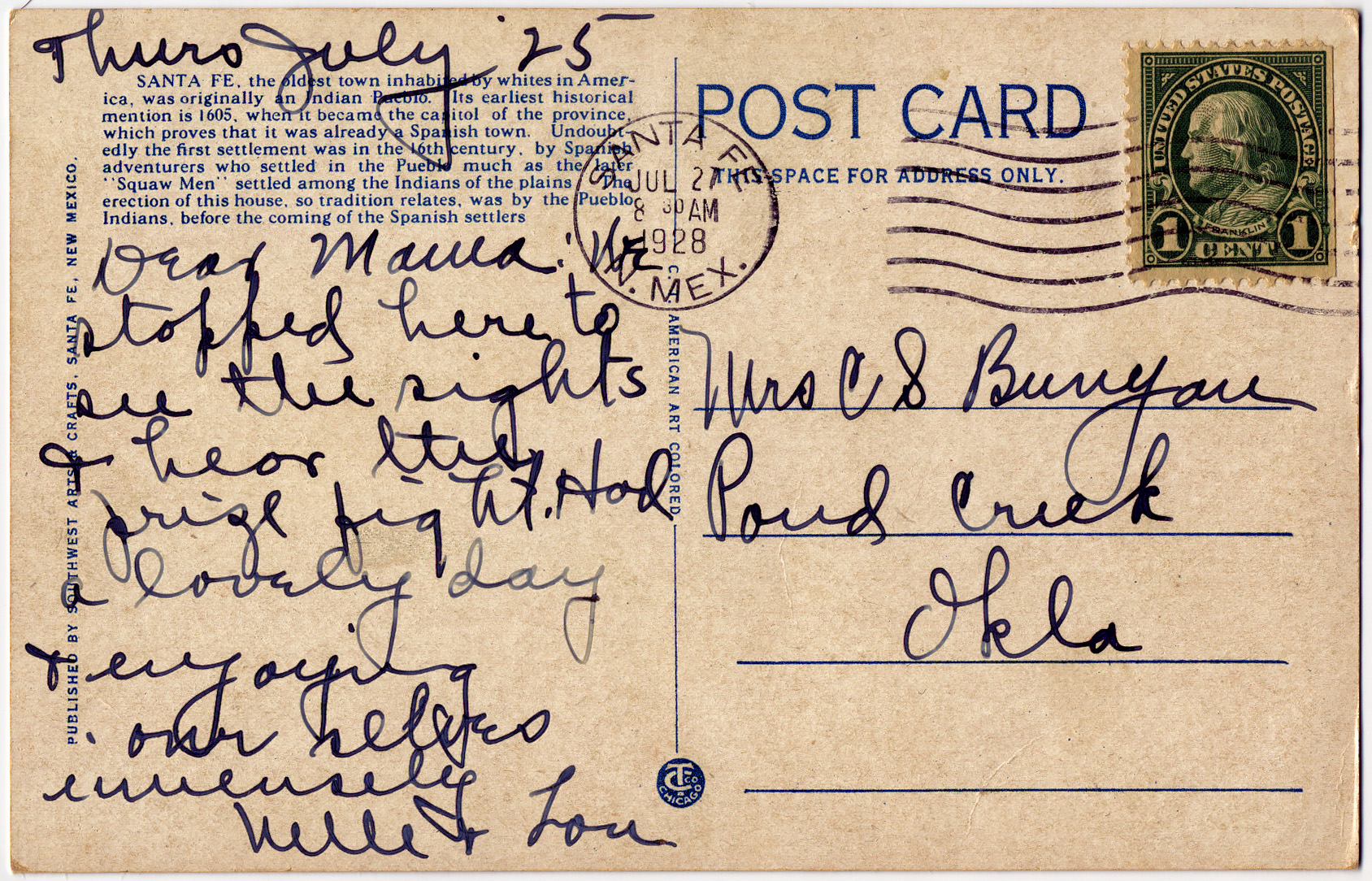

Nellie was one of the more precocious and engaging children of the Bunyan clan. Upon graduating high school she launched into her journalism career as an editor with the Pond Creek Daily Vidette in 1903. A short two years later she took a job writing for the society column at the larger Guthrie Leader newspaper. There she covered the casual goings on about town and other important meetings and events that occurred. She would in later years became the music editor.

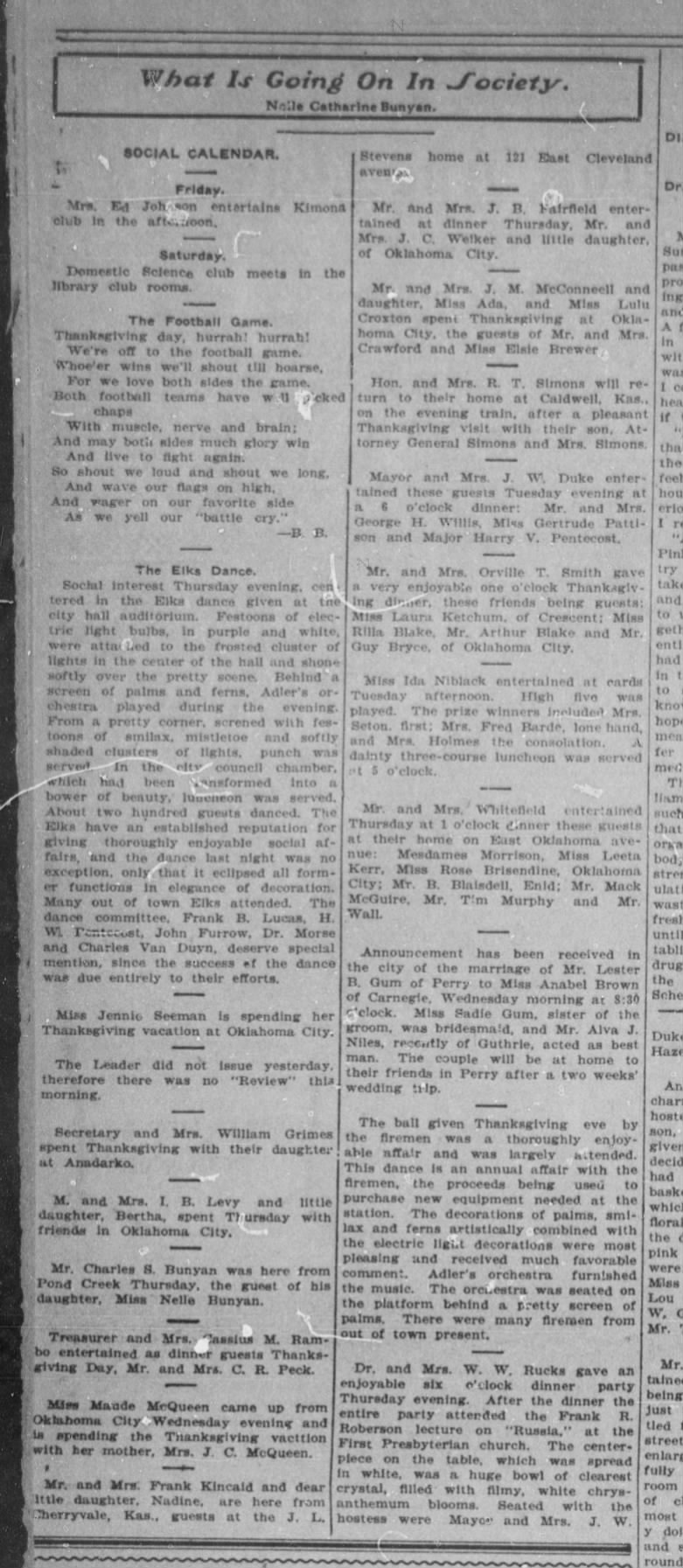

At the age of 20 in late summer 1906, Nellie attended a game of base-ball in the company of friends. There she met the player/manager of the local Lawton independent club—a team that would go on to take the territorial championship pennant that season—Frank Jennings. Jennings was a local attorney and businessman with a storied past. He must have made quite an impression on Nellie. A few days following their meeting, they were introduced once more at a party held at the home of U.S. Marshall John R. Abernathy, a friend of Charles Bunyan, in Logan, OK. That very night Frank proposed marriage on the spot. To his surprise, Nellie accepted.

They were married the first of October in an evening garden ceremony at the Abernathy home, two weeks from the day they first met at the baseball game. The lovers “beneath a great elm tree on the lawn, kneeling on the velvety grass plighted their troth.” This was in keeping with a superstition that the life of a couple married by the light from the full harvest moon would be blessed with years of good fortune. They would certainly share interesting days to come.

The story shocked Nellie’s society and journalism friends for its suddenness and its secretive nature. She kept her closest friends and associates in the dark. Nevertheless, there are two full accounts of the wedding nuptials appearing in both the Guthrie Daily Leader and the Los Angeles Herald newspapers a few weeks later.

[You may be asking yourself at this point, “Los Angeles Herald?” Why would a small town wedding generate interest in the growing metropolis of Los Angeles? It has something to do with the fact that Frank Jennings and his brother, Al, were notorious outlaws in a previous life. There will be more to say about that later.]

Shortly after their wedding, the young Jennings couple boarded up their house and built a home in the growing frontier town of Estancia, New Mexico. Once there, Frank established a law practice and set out his shingle, “Frank Jennings, lawyer”.

He quickly established himself with the political groups of the day, and at one point just missed being on the official New Mexico Statehood Convention Committee by a few dozen votes. He nevertheless worked tirelessly on matters related to New Mexico becoming a state, going so far as drafting legislation for the U.S. Congress to consider. He was frequently in both Santa Fe and Albuquerque for matters related to this work as well as cases he was handling for the local citizenry back in Torrance County. His name appears quite often in local papers of the day, including The Santa Fe New Mexican and the Albuquerque Journal.

While in New Mexico they gave birth to a daughter who died shortly after childbirth. Soon afterwards they had a son, Alphonso Frank Jennings (“Frank, Jr.”) in July 1907.

New Mexico obtained statehood in 1912 and a year later, in 1913, their home in Estancia caught fire and burned. An article mentions that they planned to rebuild but to what extent they remained there full time is a mystery. Nellie and Frank Jr. returned to Oklahoma, as did Frank senior a short time later. By the mid teens oil was the hot venture in the Oklahoma region. Frank wasted no time establishing a well on his land and acquired leases with several other nearby ranchers and farmers to drill on their sites. From that point onwards he was an oil man. The Jennings Petroleum Company was founded, with Frank, Nellie, and Frank’s brother Al Jennings as the initial founders.

It quickly became a rising star among the dozens of wildcat outfits in the territory. Nellie took to writing once again for the Guthrie Daily Leader under the byline “Nelle B. Jennings”. Meanwhile, the oil income allowed for a new venture that would come to place the family in the public spotlight, mostly to Nellie’s chagrin. Before getting into that, however, I need to backup a bit and talk about Frank Jennings’ outlaw days.

The Jennings Outlaw Gang

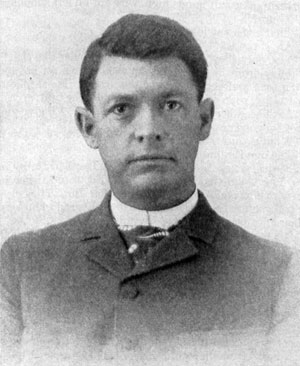

Alphonso “Al” and Frank Jennings were two brothers who left home in Virginia to make it big out west in the late 1800s.

Franklin Frasier Jennings was born in Virginia on 25 September 1861 to John Dela Fletcher and Mary (Scates) Jennings. J. D. F. Jennings was a methodist minister, lawyer, and eventual Oklahoma territorial judge. Frank’s younger brother, Al, was born two years later on 25 November 1863. Though the youngest son of the Jennings brothers, Al was the loudest, most outspoken child of the bunch.

They were a rogue pair of trouble makers in their youth when, about 1874, they decided to head west, leaving the family behind. Al was all of 11 years old. They passed through St. Louis, Kansas City, and eventually landed in Trinidad, Colorado. Based on Al’s own colorful telling of his life story, they boys returned to Virginia in 1880 and studied law at West Virginia State University. The family moved westward and both were admitted to the Kansas bar. They settled in the Oklahoma territory in 1889 in Reno, OK. Al ran for the attorney of Canadian County and won. He served one term before losing out on the next election cycle. In 1894 he moved to Woodward, OK, and set up a law practice with the oldest Jennings brother, John, and another brother, Ed Jennings. Their father, J. D. F. Jennings was a territorial judge in Oklahoma by this time.

The Jennings brothers encountered trouble in Oklahoma almost from the start. A running feud commenced some time around 1894 between the Jennings brothers and another Woodward lawyer named Temple Houston, youngest son of famed Texas Gen. Sam Houston. The feud came to a head on October 8th, 1895, from an insult Temple Houston lobbed at Ed Jennings during court proceedings. They were lawyers on opposite sides of a case in which Ed Jennings was defending some men accused of theft and Jennings had questioned the the admissibility of a key witness’ testimony.

Houston retorted that Jennings was “grossly ignorant of the law.” Jennings moved to slap Houston, Houston drew a gun, but before shots were fired court personnel broke up the fight. Proceedings were immediately suspended and the case recessed until the following day.

Around 10pm that evening, however, John, Ed, and Al Jennings encountered Temple Houston and Woodward County sheriff Jack Love in Jack Garvey’s Cabinet Saloon. A fight broke out and guns were drawn and this time shots were fired. In the end Ed Jennings lay dead from a bullet fired by Love. John lay wounded with a bullet in his arm fired by Houston.

Jack Love and Temple Houston were charged with manslaughter. During court proceedings, their defense revolved around testimony that Ed Jennings was first to fire a shot and they returned fire in self defense. Testimony was further bolstered by a deposition given by Walter Younger, a printer for the Woodward News, who was in the shop that abutted the rear of the saloon on the night of the shooting. Younger overheard conversation from John Jennings and a cousin, “Handsome” Harry, just outside of the saloon and before John first entered. The words Younger heard were, “For God’s sake, give me a gun.” This was enough to convince the jury that the Jennings brothers had gone in looking for a fight. Houston and Love were eventually acquitted of murder.

Al Jennings did not wait for the trial to commence, let alone end, to extract his revenge. On the day his brother John was buried he grew more and more agitated. He and his father exchanged words and the elder admonished his son to the effect that he was acting foolish. Al gathered up his belongings and left in anger. Soon thereafter he held up a grocery store and, with Frank joining him, they set off on their life of crime.

Years later, when asked about it, Al Jennings blamed this on the chivalry of the male southerner. “That high, proud, overbearing blood has a lot to do with the way I acted. When such people are picked on, they believe in their bones that it’s right to tear up the whole earth to get even.”

They brothers engaged in low-level cattle rustling while working as ranch-hands across the west. Some time in 1897 they teamed up with childhood friends and brothers—Patrick and Morris O’Malley, and a fifth companion, Richard “Little Dick” West. Over the span of a few short months the group became full-fledged, if not comical, outlaws.

Their first attempt at train robbery occurred in early August of that year when they tried to rob a train stopped in Edmond, OK. The plan was swiftly aborted when the train’s conductor recognized Al and even called him out by name.

At the end of the month, on August 30th, they tried to force a train to stop somewhere between Muskogee and Oktaha by piling railroad ties on the tracks ahead of the train. The conductor spotted the pile and applied more speed and simply rammed through.

After setting train robbery aside they next decided to hit up the American Railway Express Company office in Purcell, OK. They outted themselves when, faces masked, they peaked through the windows of the office to scout the place out before entering. They were spotted by an agent who made quick use of the new telephone that had been installed. The town marshal with a few armed citizens in tow quickly arrived just as the gang of five managed to make their escape.

At the end of September the following month they planned to hold up a bank in Minco, OK, but Al’s propensity to blab about the gang’s exploits somehow made it ahead of them. They arrived at the bank on the morning of the planned heist only to find it surrounded by guards on the lookout for the gang. They rode through town without stopping and kept going.

They returned back to the idea of robbing trains and on October 1st, they had their first success of sorts. A train stopped for water north of Chickasha, OK, and the gang boarded and quickly robbed passengers and crew of some $300 in cash and a $15 silver pocket watch. Their real goal was to break into the safes. Trains typically had two safes aboard, a “through” safe which was locked before the train left a station and could only be unlocked by a destination agent or other remote agents at designated stops, but not by any crew person on the train. The other was a “way” safe used for temporary storage of passenger valuables and other crew uses. The Jennings-O’Malley gang attempted to gain entry into the safes using dynamite. They piled several sticks atop the through safe and then placed the way safe atop that. Al explained to Frank that one needed lots of dynamite to “dent a big safe like that”. The resulting explosion reduced the baggage car to splinters but did nothing to dent either safe. It did blow the way safe some 30 feet away. [The telling of this fiasco was repeated far and wide and was the basis for a similarly humorous scene in the film “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid”.] The gang had to content themselves with the $300 dollars, the watch, and a new pair of boots they fleeced from a traveling salesman aboard the train.

They stuck to robbing general stores and grocery stores to feed themselves for the next month but struck a US post office in Foyil, OK, on November 20th. They nabbed $300 from the till and placed it into a mail sack along with a small amount of cash taken from customers. They gave it all back inadvertently when they made their escape and grabbed the wrong mail sack on the way out.

Though unsuccessful in securing the fortunes they sought, the gang had made themselves known to railroad companies by this time and were considered a dangerous nuisance. A reward of $100 was offered for each member.

The way Al Jennings told it later in his flamboyant autobiography, scores of lawmen were in hot pursuit of the gang. The simple fact was that only one man, the infamous US marshal and territorial deputy from Muskogee County, James Franklin “Bud” Ledbetter, was after the men, along with a skeleton posse of a few able men.

Ledbetter tracked the gang from a store robbery in Cushing, OK, and the Foyil post office near-heist, and figured the gang was heading towards the Spike-S Ranch to hide out for a while.

Ledbetter and his men rode out to the ranch and surrounded it one morning in November. Dick West had since left the gang in disgust but the two Jennings brothers and the two O’Malley brothers were inside the house when a ranch worker made it known that they were surrounded. A 15-minute gun battle ensued with more than 300 bullets flying in all directions. Only one hit flesh and Morris O’Malley was wounded in the leg. The others managed to make an escape amid the confusion, leaving behind the wounded man. Morris gave up their next meeting location, Rock Creek Crossing, and Ledbetter raced ahead of them.

The gang of three arrived at Rock Creek Crossing on December 6th, 1897, and were swiftly apprehended by Ledbetter and the posse.

Following trials, Frank Jennings and the two O’Malley brothers were sentenced to five years in prison. Al, for his role as the ring-leader, by his own boisterous admission, was sentenced to life in prison for assault with intent to kill a law officer and the robbery of the sack of US mail. He was sent to the Ohio State Penitentiary in Columbus, OH. As for Little Dick West, he was tracked down to a hideout near Tulsa, OK, a few weeks after the apprehension of the Jennings gang but died in a shootout with officers. In all, their outlaw career lasted a span of 108 days.

Al served five years in prison before his sentence was commuted and he was freed in 1903, largely through his father’s connections in Oklahoma and family friend, Senator Mark Hanna of Ohio, who appealed directly to President McKinley for the release. (Later in 1907, after another intervention by President Roosevelt, he and his brother Frank had their full citizenship, including voting rights, restored.) Frank was released around 1902 and returned to practicing law in Lawton, Oklahoma.

Among the men in Al Jennings’ cell block at the penitentiary was a bank teller serving a three year stint for embezzlement, William Sydney Porter. Porter had been a struggling author who had taken various odd jobs in his early years to support his writing projects, notably a short lived magazine titled Rolling Stone. (He was also a licensed pharmacist and served in the prison hospital in that capacity, earning him an early release.) In Porter, Al Jennings found a most attentive listener to his tall tales of banditry and train robbing. By 1904, Porter was freed from prison and had begun penning stories under the pseudonym he would use the rest of his life—O. Henry. His conversations with Jennings lead to his story Holding Up A Train (1904) and the book The Roads We Take (1910). The opening paragraph to Holding Up A Train contains the following note.

Note. The man who told me these things was for several years an outlaw in the Southwest and a follower of the pursuit he so frankly describes. His description of the modus operandi should prove interesting, his counsel of value to the potential passenger in some future “hold-up,” while his estimate of the pleasures of train robbing will hardly induce any one to adopt it as a profession. I give the story in almost exactly his own words. O. H.

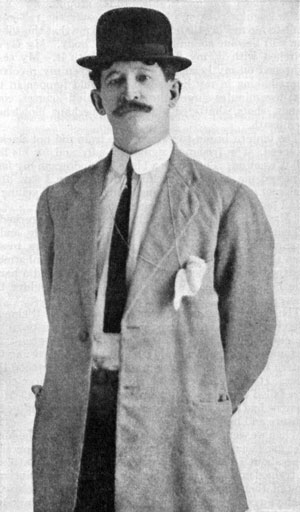

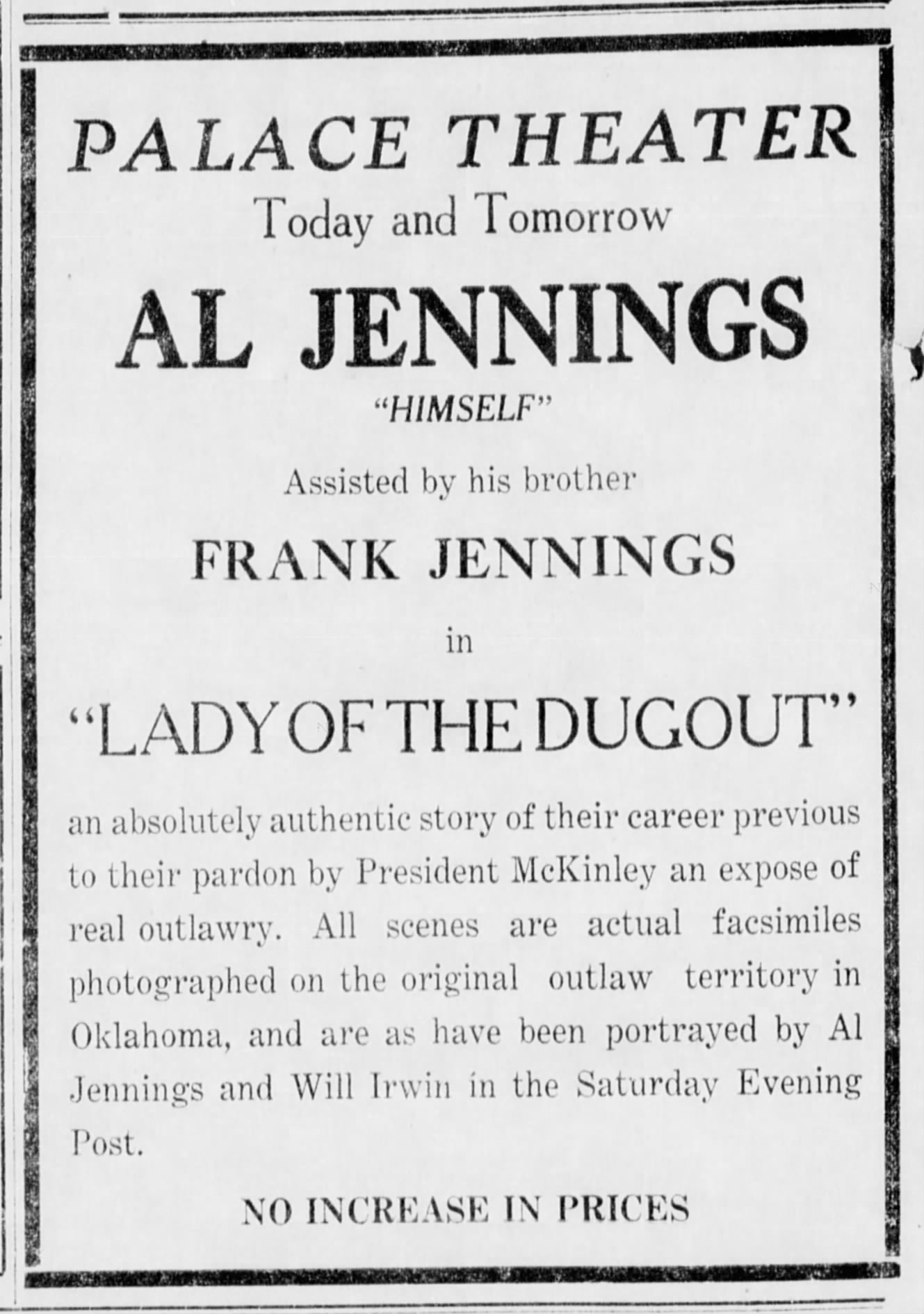

Also during his time in prison, Al Jennings saw the 1903 silent film, “The Great Train Robbery”. It had been filmed “on location” in New Jersey and New York’s Central Park though it aimed to depict the wild west. The phoniness of the film location and the presentation of “western” train robberies didn’t sit right with him. Being the boisterous man he was, he decided to get into the movie business and show those fools just what the “Wild West” was truly like. Who best to tell these tales than the man who once bested Jesse James in a gunfight, robbed more trains than anyone, and killed more men than Billy the Kid?

Very soon after his release from prison, Al Jennings headed to Hollywood where he managed to convince enough film people that he was an expert on bank and train robbery, and the life of bandits and the west in general. He had a hand in creating the 1908 silent film, “The Bank Robbery”. In fact, the film’s director was former US marshal Bill Tilghman, one of the men involved in the pursuit and death of Little Dick West. Al Jennings spent a few years in Hollywood and next returned to Oklahoma to capitalize on his growing fame and reputation as a turned-around bandit. He ran an unsuccessful campaign for prosecuting attorney of Oklahoma County in 1912.

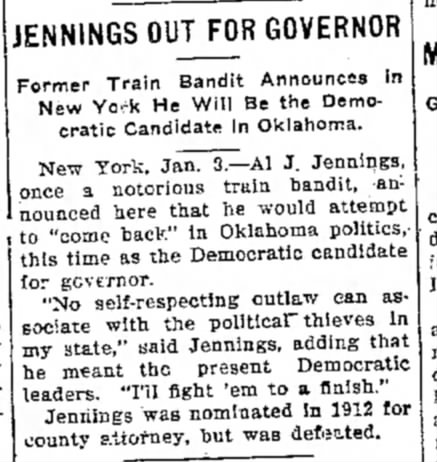

By 1913, his life story had been reshaped into that of a modern day Robin Hood. He decided to tell his story in a serialized piece that ran in The Saturday Evening Post under the title “Beating Back”. With his continued fame, he launched a campaign for governor of Oklahoma in 1914, but also lost.

He returned to Hollywood after this and his next film, based on his Post stories, was released at the end of 1914. “Beating Back” glorified the life of the outlaw, much to the chagrin of US marshals and the men who helped bring Jennings to justice. They decided to strike back and formed the Eagle Film Company to produce their own film, “The Passing of the Oklahoma Outlaws” in 1915. Oddly enough, Al Jennings played himself in the latter film.

Al Jennings spent the rest of his life as an actor and film producer and occasional preacher during a spell where he “found religion.” After co-founding the Jennings Petroleum Company with his brother Frank, they used their profit to produce more films. Eventually Frank headed out to California as well, though it isn’t clear when nor for how long. Frank Jennings, Jr. also settled in California and became involved with live theater and remained there for the rest of his life.

Not much is known of Frank Jennings after 1920. He played the sheriff in the last film to his credit, 1929’s “The Three Outcasts”. Whether he retained some involvement in the Jennings Petroleum Company is undetermined.

Teapot Dome Scandal

The only mention of Jennings Petroleum Company in the news during these years is in 1924 when Al Jennings was subpoenaed to appear before the US Senate in matters related to the infamous Teapot Dome Scandal.

In March 1921, newly sworn-in President Warren G. Harding named New Mexico Senator Albert Bacon Fall as his secretary of the interior. (Incidentally, Fall had been elected as New Mexico’s first US Senator, following its acceptance into statehood in 1912. There is reason to suspect he would have crossed paths with Frank and Al Jennings.) Once in a position of influence, Fall accepted some $385,000 in bribes from two friends—Oklahoma oilman Harry F. Sinclair and another oilman from California, Edward L. Dohney—in exchange for lucrative, no-bid leases to drill at strategic Naval oil reserves in Elk Hills, California and Teapot Dome, Wyoming. Fall also accepted a $100,000 loan to build a home in New Mexico.

The Wall Street Journal reported the scandal in April 1922. A subsequent investigation found Fall guilty of conspiracy and bribery, and as a result, he ended up spending a year in prison for his role.

Though Jennings Petroleum was not one of the oil companies involved, the Jennings did know and interact with several of the key characters related to that scandal since most of the principal players were based out of Oklahoma. One of those was a man believed to have orchestrated the whole affair along with other nefarious acts surrounding the Harding administration, Jake Louis Hamon. Hamon was also a resident of Lawton. In fact, he was its first attorney general, having been elected after the town was established following the 1901 Oklahoma Land Lottery. (Lawton was formed around Fort Sill, famous for its band of Apache prisoners at the time, including the legendary Chief Geronimo who passed away there in February 1909.) He was voted out of office in 1903 after it surfaced that he extorted money from local gambling outfits in exchange for protection. This was during the years the Frank and Al Jennings returned to the region to restart their law practices.

Like many notable men of the day, Jake Hamon participated in oil speculation and obtained thousands of dollars in questionable loans to get started. He struck it rich in the Healdton oil field and amassed some $3 million in the span of two years.

He rose to power in Oklahoman Republican circles and found his way onto the executive committee of Harding’s election campaign. He used his influence to obtain positions for many notable figures of the day and it was Hamon, himself, who was widely believed would be offered the position of Secretary of the Interior. Unfortunately, following a private meeting at the Ardmore Hotel with a member of president-elect Harding’s staff to discuss just what this would be, Hamon was shot by his young mistress, 23 year old Clara Smith Hamon. [To pass Clara off as his wife when checking into hotels—and because Jake was already married—Hamon paid his nephew, Frank Hamon, $10,000 to marry Clara and then disappear to San Francisco, hence her last name.] He suffered in the local sanitarium for 5 days before dying, on 26 November 1920.

It is interesting to me that Frank is never mentioned in any of the Teapot Dome articles and that as the head of his oil company, it wasn’t he that was called to testify. Perhaps he had left his own company when he headed out to California.

Nellie Moves On

In any event, Nelle had become more involved with women’s suffrage issues. Following the passing of the 19th amendment in 1920, she worked to educate women in matters related to politics. She wrote in-depth articles covering women in Oklahoma politics like this one that appeared in Harlow’s Weekly in 1921.

She used her maiden name on a book she released in 1924, Handbook For Women Voters, suggesting that she was already divorced from Frank by then. By 1928, Nelle was single, living in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and writing as the music editor for the Tulsa Tribune when on 20 July 1928 she married Leonidas “Lon” William Hardwick (b. 15 January 1880), a court reporter in Tulsa. They were on their honeymoon traveling through the southwest when they stopped in Santa Fe to listen to a prize fight.

The Prize Fight

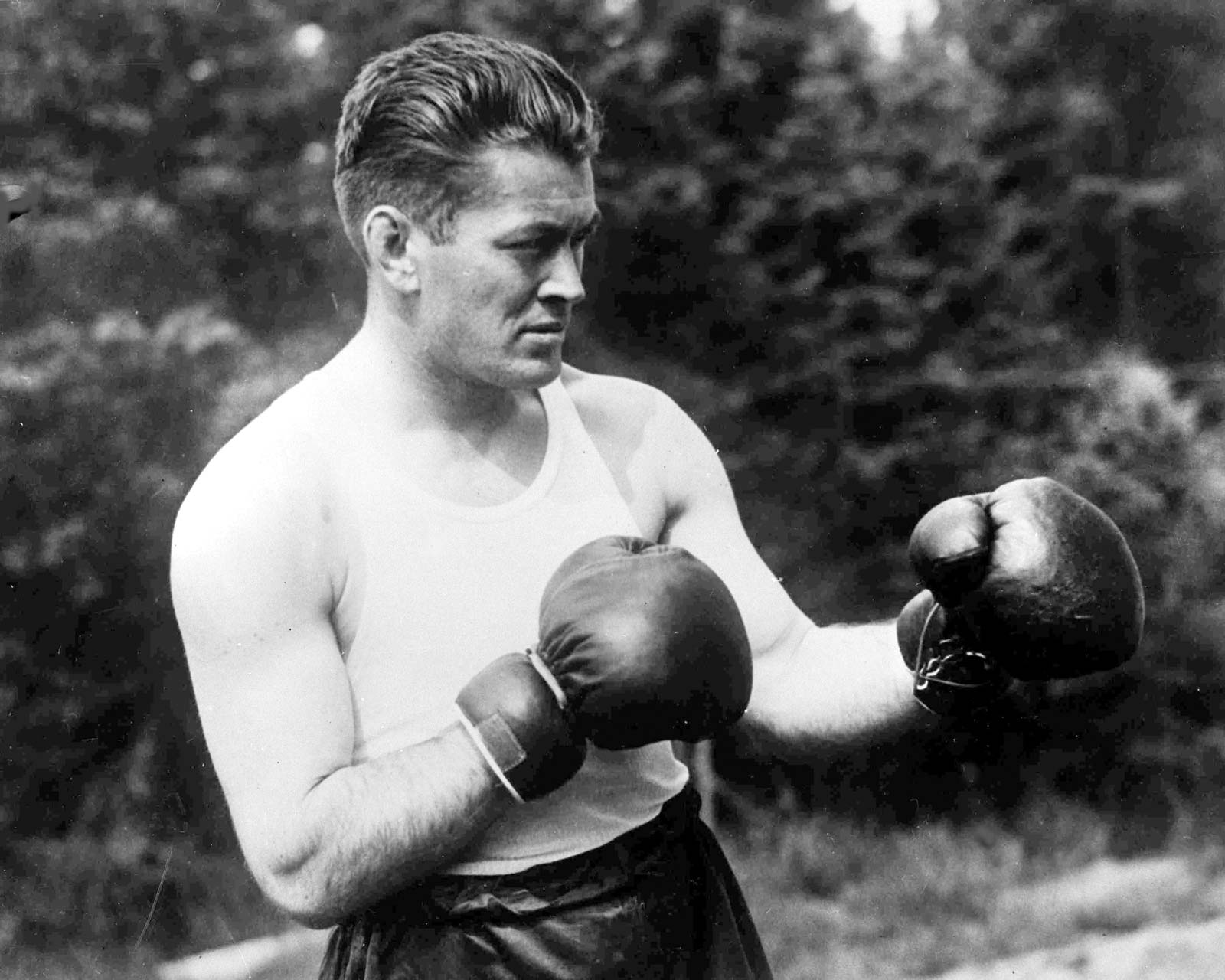

This is the “prize fight” mentioned in the postcard. The fight was a famous matchup between then heavyweight champ Gene Tunney, the beloved Fighting Marine, a nickname acquired from his days boxing in his former marine platoon during WWI.

His challenger was New Zealand boxer Tom Heeney. The fight was arranged by the none other than boxing promoter Tex Rickard.

George Lewis “Tex” Rickard was a successful promoter back in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Also born in Kansas City, Missouri, but raised in Texas from the age of 4, Tex grew up with an appreciation for hard work and the frontier lifestyle. With the first news of possible gold in Alaska he headed to that territory to find wealth. He and a partner, Harry Ash, were already in the region when news of the Klondike strike first hit. They staked a few claims and did make a small fortune from gold mining and a slightly larger fortune by establishing the “Northern”, a hotel and gambling saloon in Dawson City, Yukon, Canada. Unfortunately he lost everything within a few years due to a gambling addiction. Broke, he headed to Nome, Alaska for another shot at gold prospecting. While there he started promoting boxing matches in the towns and camps around Nome. He re-established the Northern for such purposes and he made a friend of Wyatt Earp—a fellow boxing enthusiast and, it turned out, a boxing officiator. It was likely Earp who caused Rickard to abandon gold mining altogether and become a full-time promoter. He left Alaska and, in 1906, he had opened the Northern once again, this time in Goldfield, Nevada. One of his earliest bouts set a record of $68,000 in ticket sales, the most of any fight in the nation at that point. It began a streak of many such records. His success landed him the rights to promote the 1909 heavyweight championship fight between James J. Jeffries and Jack Johnson. The fight was held in Reno, Nevada, and earned Tex and his partner $120,000 after expenses.

Eventually Tex ended up in New York city and established an exclusive 10 year lease on Madison Square Garden for boxing matches. At the height of this period he set his best record for the Jack Dempsey–Bill Brennan fight, on December 14, 1920. The gate intake exceeded a staggering $2 million and earned Rickard just over half a million dollars for himself.

It was during this period that he set up the match between heavyweight champion Gene “the Fighting Marine” Tunney and challenger, Tom Heeney. He promoted this fight at Yankee Stadium and he had worried about selling to such a large venue. The match was the talk of the nation beginning with its announcement in April of 1928 up to the day of the fight. Tunney, you see, had only recently become the world heavyweight champ when he defeated fan-favorite, Jack Dempsey, in another fight promoted by Rickard in 1926 and again in a rematch in 1927.

On 26 July, 1928, Tunney achieved a technical knockout 2 minutes and 52 seconds into the 11th of 15 scheduled rounds to retain the world heavyweight title. Archived video and audio of a portion of this fight can be seen on YouTube.

This proved to be Tunney’s last fight. As a boxer he never caught on with fans. Dempsey was a famous killing machine whereas Tunney used skill over braun and brought logic to the game, making fights a technical battle if you will. On the fist title fight with Jack Dempsey he told a reporter, “I did six years of planning to win the championship from Jack Dempsey.” He went to boxing matches and studied newsreel footage to learn how to defeat his opponents. He won bouts via technical knockouts, never “going in for the kill”, much to the chagrin of boxing spectators. To make matters worse, Tunney was educated. It came out that he enjoyed reading Shakespeare and sports writers got in their own jabs with this information. Even the humorist Will Rogers got one in when he wrote, “Let’s have prizefighters with harder wallops and less Shakespeare.”

After two years as the heavyweight champion (during which he married the wealthy heiress Polly Lauder) he had amassed enough of a fortune to forgo the sport entirely, devoting the rest o this life to other business and cultural pursuits. His final record was 80-1 with 48 knockouts.

In addition to promoting boxing, Tex Rickard had plans for bringing star-quality hockey to New York. With partners, they managed to purchase the land on which Madison Square Garden was located. The building was raised and a third generation MSG was built. In 1926, Tex Rickard and the Madison Corporation were given a National Hockey League franchise and they founded a new hockey team, also making its home at MSG. Tex’s Rangers, today known simply as The Rangers, play exclusively at the MSG for their home games to this day.

Epilogue

Nelle lived a mostly quiet life in her later years. She and Lon had settled in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where she continued her journalism career as the music editor for the Tulsa Tribune. Lon died unexpectedly on 20 July 1931 at the age of 52, around the time of their third anniversary. Following Lon’s passing, she wrote freelance pieces for the Fairchild News Service and the All-Church Press, while still contributing regular columns for the Tribune. She was engaged in the community and served on several civic boards, including the Civic Music Association in Tulsa. She passed away on 17 June 1965 from cancer.

When Lon Hardwick passed away in 1931 he was in the middle of transcribing notes from a local murder case in which the defendant, Chester Stone, had received a life sentence with no chance of parole. The case was under appeal and Hardwick’s death cause unnecessary delay in presenting the casemade. Since Hardwick was the only person capable of doing the transcription, it lead to Stone getting an an entirely new trial. He received a better outcome the second time, a 7 year sentence. He was paroled in early 1936 but on the evening of 11 October, he served as a lookout in which accomplices robbed a man of $70. He fled to Miami, FL, afterwards but was identified by witnesses. A warrant was issued and he was finally arrested and extradited back to Tulsa for trial in 1938, where he received an 12 year sentence.

In 1945, a bandit character loosely based on, and even named Al Jennings, was featured in the Lone Ranger radio program. In the story, the masked avenger shoots a gun out of Al’s hand. Jennings sued the production company behind the show and lost. He settled in Tarzana, California and spent the rest of his days telling his stories to anyone who would listen. A final film was made about his life, “Al Jennings of Oklahoma” was released in 1951 by Columbia pictures.

He passed away at the age of 97 on 26 December, 1961.

Frank Jennings, Jr. served as a military MP during WWII and returned to Los Angeles following the war and worked as a newspaper photographer. He died of unknown causes at the age of 45 on 28 January, 1953.

Recent Comments