Cemetery Tales: The Japanese Internment Camp Detainees of Santa Fe

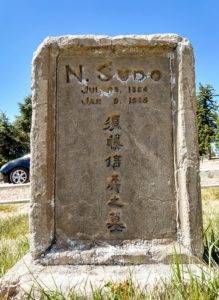

A reader sent me the photo of a grave stone with Japanese characters and asked if I knew any details about it. Their (correct) assumption was that the tombstone was related to the victims of the Japanese internment camp located in Santa Fe during World War II. What follows is a bit of a history lesson for those who may not know about this era of Santa Fe history.

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the nation was in shock and its citizens flooded with an overwhelming sense of vulnerability. The fear was no more palpable than on the west coast—California, Oregon, and Washington. Thoughts quickly moved from where the next attack might occur to mobilizing everyone to protect basic infrastructure facilities—utility companies, water treatment plants, major roadways and bridges, and so on. The fear did not exist solely along the coast, however. Developer Allen Stamm was then a member of the Santa Fe sheriff’s posse. A call went out the afternoon following the attack. Every member was told to report to the sheriff’s office with two guns. “I didn’t have a single gun, but somebody loaned me a six-shooter,” Stamm recalled for a 1991 article in the Santa Fe Reporter [1]. The posse was ordered to keep watch over the local power company, the railroad bridge near Lamy, and a Japanese gardener in Tesuque.

“They were worried the Japs would take over Mexico; that they’d come marching up the Rio Grande.” —Allen Stamm

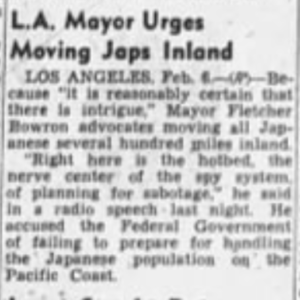

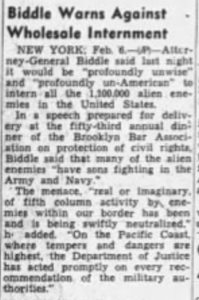

The fear against the Japanese living among us gave rise to swift, troubling actions. Earlier that day and following the attack, President Roosevelt had signed presidential proclamation 2525, declaring Japanese citizens as alien enemies under the Alien Enemies Act. He also signed proclamations 2526 and 2527 while he was at it, declaring German and Italian citizens as alien enemies, despite the fact that we would not enter war with those nations until December 11. The proclamations authorized the apprehension, restraint, and the outright removal of non-citizens from those countries. Just over two months later, on February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 authorizing the Secretary of War “to prescribe military areas in such places and of such extent as he or the appropriate Military Commander may determine, from which any or all persons may be excluded, and with respect to which, the right of any person to enter, remain in, or leave shall be subject to whatever restrictions the Secretary of War or the appropriate Military Commander may impose in his discretion.” This led to the creation of a vast number of Japanese internment camps throughout the interior of the country—Santa Fe included—whereby some 117,000 people of Japanese ancestry, mostly from the Pacific coast, were forced to leave jobs, homes, personal belongings, and even other family members, to be relocated by force to live within the camps. Political opposition against the measures was small and in the minority.

Data published long after the war ended revealed that some 62% of the detainees were US citizens. It wasn’t revealed until the 21st century that US Census data was used to round up many of these people.

The atrocities suffered by these people is a story told elsewhere. This tale is about the unique interment camp to Santa Fe.

Besides getting the sheriff’s posse on board to monitor local Japanese residents some 200 tents were erected on the site of a former Civilian Conservation Corp campground where the Casa Solana neighborhood sits today. The land was put under the control of the New Mexico Prison Board. The tents were temporary facilities until the construction of 24 barracks was completed at the beginning of March 1942. The first trainload of detainees arrived on March 14, 1942.

“They came to into Santa Fe station [Lamy] on trains in the deep dead of midnight. They were put on trucks and taken to camp. All we knew was to pick them up and sort them out in a 24-hour cycle…But there was no reason for them to be interned. They were in the wrong place at the wrong time.” —Frances Ortega, former camp stenotypist.

The camp was built to house 2,100 detainees at a time and 100 full-time guards. By war’s end, some 4,500 men would be detained there. Santa Fe’s camp was unique in that it only housed Issei men, [Issei (一世, “first generation”), natives born in Japan but that had immigrated to the US. The term specifically applied to Japanese nationals who arrived from 1885 up through 1924, when the Asian Exclusion Act (part of the 1924 Immigration Reform Law) prohibited further non-whites from legally immigrating to the country. The food supply in camp was quite limited even though much of the produce was grown by the detainees themselves. The water supply was wrought with mosquito larva and hospital facilities were overwhelmed.

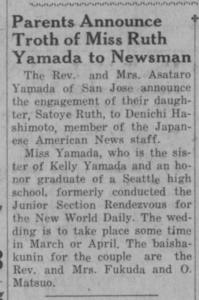

Aside from the substandard living conditions was the horrific effect on families. Men were stripped away from wives and children, held in camps elsewhere. The unfounded reasoning and horridness of it all was no better illustrated than in families such as that of Satoye Ruth Yamada Hashimoto (b. 10 Nov 1913, Seattle, Washington; d. 4 Jan 2010, Rio Rancho, New Mexico). She was a US citizen born in Seattle, Washington, yet detained at the camp near Heart Mountain, Wyoming. Her father, an issei, was sent to Santa Fe, at the age of 64. Her brother Kelly Yamada, however, was serving in the US Army, having enlisted long before Pearl Harbor. They were prominent members of the San Jose, California community until the war broke out.In all, some 42 incarcerated Japanese died while being forced to live at the Santa Fe camps (1,862 Japanese died in camps nationwide). At least two of them were buried in Rosario Cemetery, adjacent to the Santa Fe National Cemetery in a small field that is known as a Potter’s Field of sorts. It is possible that more, unmarked detainee remains are buried there.

The cover photo for this piece is the backside of one of two known graves, that of one Nobuyoshi Sudo (b. 23 July 1884, Fukuoka-shi, Fukuoka-ken, Japan; d. 9 Jan 1945, Santa Fe, NM) a 60-year old railyard worker living in Harahan, Louisiana at the time of his internment.

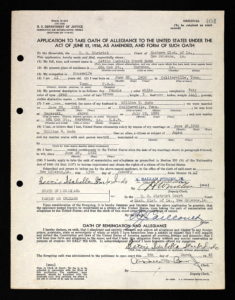

He left behind his American born wife, Zettie Isabella (née Stork) from Tennessee and two American born sons, 19-year old Nile and 10-year-old Victor. So immersed was he in American culture that he chose to go by the name “William” on his employment and Census records starting around 1930, and on his official naturalization papers—signed and approved just a few months before his arrest—on 13 January, 1942.

The other known grave is that of Gentaro Yoshikawa (b. 27 December 1881, Koshi-ken, Japan; d. 6 June 1945, Santa Fe, NM), a 62-year old US Naval laundry worker living in Vallejo, California at the time of his arrest and subsequent relocation. His charge, on February 6, 1942, was for possessing Navy signal flags—items he would have normally possessed.

Nothing remains of the internment camp in Santa Fe. The last of the 89 detainees were shipped out and it was officially closed on April 23, 1946. The land was auctioned off by the New Mexico Prison Board in 1953 and purchased by none-other than Allen Stamm for the sum of $98,000. The Stamm homes in the Casa Solana neighborhood are sought-after homes to this day, given the views afforded from the hillside.

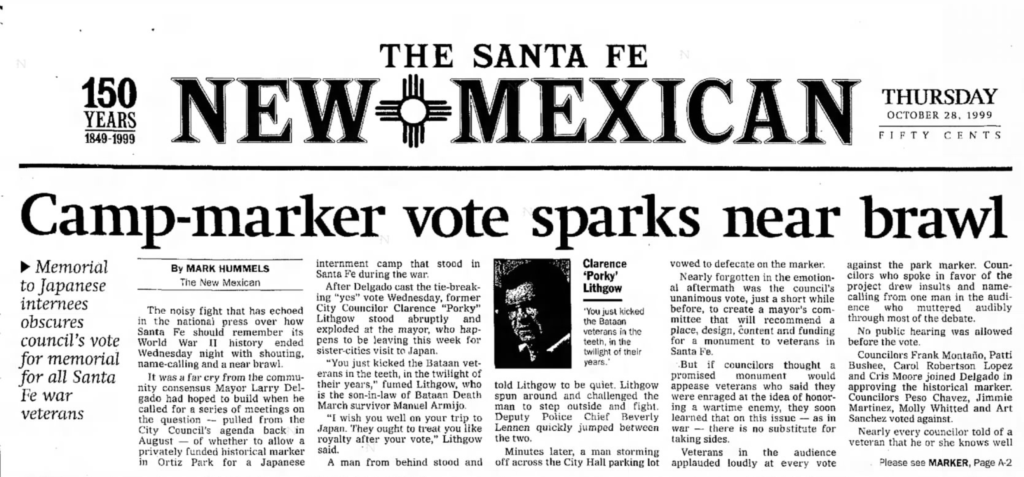

In 1999 the City of Santa Fe City Council voted on a measure to erect a monument to the camp. The Council was locked in a tie following a contentious and nearly violent outburst from Council members as well as audience members. This lead to then-Mayor Larry Delgado casting the deciding vote. The stone monument sits in Frank S. Ortiz Park, the closest spot to the former site of the camp. [1] The Years of “Los Japos”, Santa Fe Reporter, July 10-16, 1991, p17-19.

Recent Comments