Cemetery Tales: The Odd Sandstone Tombstone in the Santa Fe National Cemetery

I recently started taking cemetery photos for the website FindAGrave.com. The site has been useful to me in my genealogy research and this is my way of giving back. The way it works is this: People make requests for photos of a gravesite for some family member or other person of interest, and the requests go out to volunteers in the area of the requested cemetery. If it is within 25 miles of me, I’ll claim the request, take the photo, and upload it to the site.

Thus far, this has given me a chance to explore two of the more interesting cemeteries in Santa Fe, the National Cemetery and the Rosario Catholic Cemetery, both on the north end of town. Some of the more famous and prominent members of the Santa Fe community are buried in these two cemeteries. Tthis gives rise to another type of posting here: Cemetery Tales. As I’m scouting for the requested photo I also get a chance to look at the more interesting monuments, names, and epitaphs found in these cemeteries. If I can find an interesting tale behind the name, I’ll post about it. This is the first such post.

The Story of the Odd Sandstone Tombstone in the Santa Fe National Cemetery

The Santa Fe National Cemetery, like all US national cemeteries, is reserved for those who have served in the military, aided the military in some capacity, or for their immediate families. Most of the headstones are standard American marble slabs, 4 inches thick, some 15 inches or so above the ground, and round at the top. The standards have been changed numerous times over the years but within sections at these cemeteries the uniformity is what leads to some of the most iconic photographs taken from their confines.

So imagine what it must be like to stroll through one of the oldest sections of Santa Fe National Cemetery and see, among the regular marble slabs rising out of the ground, this weathered sandstone sculpture atop the grave of one Private Dennis O’Leary.

What reason could there be for such an ostentatious display? Even some of the most prominent military personas of the last two centuries received ordinary marble slabs, though some had a lot more writing on them than is typical.

For example, the following notable people are buried in Santa Fe National Cemetery.

Governor Charles Bent, the first American governor of the Territory of New Mexico following the end of the Mexican-American War. Gov. Bent was killed on January 19, 1847, during a pueblo uprising in Taos. He has a basic white marble slab and is one of the few men of the era who did not serve in the military.

There is Major General Patrick J. Hurley, Secretary of War under President Herbert Hoover. He served in both WWI and WWII and he, too, only has a simple marble slab.

Next is Oliver La Farge, the Pulitzer prize winning author (Laughing Boy, 1929) and anthropologist who had settled in Santa Fe in 1933. He served in the Army Air Transport Command during WWII, and went on to champion native American causes, as well as to write a regular column for the local newspaper The Santa Fe New Mexican. He is one of Santa Fe’s better known citizens yet he, too, only has a simple marble slab.

Finally, there are numerous deserving war heroes such as Warrant Officer John W. Frink. WO Frink was killed when piloting a helicopter in Vietnam as part of a critical rescue mission into hostile territory. He was first listed as MIA from 1972-1994 and was later interred with his father, Harry Wallace Frink, in Section O, Site 371 on May 25, 1994, following a search for remains that concluded successfully that year. Their combined gravesite is marked with a single marble slab.

This Private O’Leary must be pretty important then, one would think. Yet for all the research anyone has done, there is surprisingly little known about him or why his grave site is adorned with such an auspicious monument. There is only a bit of folklore and scant information from his military service records, notably a line listing his cause of death, on 1 April 1901, at the age of 23 years and 9 months while stationed at Fort Wingate, a desert outpost due east of Gallup, New Mexico. More about that later.

According to the local folklore he carved his own tombstone, including the inscription. This is what is inscribed on the rear left side:

Dennis O’Leary,

Pvt, Co I, 23 INFTY

DIED

APL. 1, 1901,

AGE 23 Yrs. & 9 Mos.

There are two variations of Private O’Leary’s story that have been passed down repeatedly through generations of cemetery workers and volunteers. The more recent version appears on various travel blogs and related websites and in one publication, War Monuments, Museums and Library Collections of 20th Century Conflicts: A Directory of United States Sites. The earliest print version I could find is in the 11 November 1984 Santa Fe New Mexican newspaper, p. E1-E2. The story goes something like this: Young Pvt. O’Leary was a cavalry soldier stationed at Fort Wingate, a desolate outpost established in 1861 about 12 miles southeast of Gallup, New Mexico. Overwhelmed with sorrow or boredom—or both—Pvt. O’Leary left his post and went AWOL for a short spell sometime in early 1901. He later returned and was disciplined for his absence. While serving his penalty he shot himself while on duty on the very date inscribed on the tombstone but not before leaving a note imploring his fellow soldiers to retrieve an interesting artifact in the nearby hills at a location he spelled out for them. The artifact was his tombstone that he had carved during his inappropriate absence. The troops brought it back to the Fort and it was used as O’Leary’s tombstone following his burial. The author of the article states that he first heard this legend from a cemetery caretaker in 1935.

An earlier version of Private O’Leary’s demise appears in the New Mexican, 12 January 1958, p. 11.

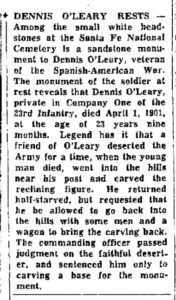

DENNIS O’LEARY RESTS—

Among the small white headstones at the Santa Fe National Cemetery is a sandstone monument to Dennis O’Leary, veteran of the Spanish-American War. The monument of the soldier at rest reveals that Dennis O’Leary, private in Company One of the 23rd Infantry, died April 1, 1901, at the age of 23 years nine months. Legend has it that a friend of O’Leary deserted the Army for a time when the young man died, went into the hills near his post and carved the reclining figure. He returned half-starved, but requested that he be allowed to go back into the hills with some men and a wagon to bring the carving back. The commanding officer passed judgement on the faithful deserter, and sentenced him only to carving a base for the monument.

To my ears this latter story sounds more plausible, notably because it is an earlier tale that precedes the modern one by nearly 30 years. A lot changes to a story over that amount of time and it is possible that the author of the 1984 article mis-remembered what he had heard earlier from the old caretaker, who also had only heard the story second-hand.

What we do know as fact comes from Private Dennis O’Leary’s military record and supports something closer to the second tale above. Dennis O’Leary was born in July 1877, in Bantry, County Cork, Ireland. He first enlisted in the U.S. Army in Grass Valley, California on 24 June 1898 and mustered out of the army 16 January 1899 at the Vancouver barracks, Washington. He then re-enlisted less than a month later, on 6 February, 1899 in Portland, Oregon. During this time he fought in the Spanish-American War with Battery A, First Battalion California, Heavy Artillery Unit, and saw action in the Philippines as part of Comopany I, 23rd Infantry.

Company I of the 23rd Infantry returned from the Philippines in the fall of 1900 and the men were stationed at Fort Douglas, near Salt Lake City, Utah. At the end of March 1901 they were redeployed to Fort Wingate, an outpost in decline that would be shut down within a few years.

Company I, 23rd Infantry under the command of 2nd Lt. Charles L. Woodhouse leave for Ft. Wingate

[The Salt Lake Herald, 21 March 1901, p. 2]

However, it also means Pvt. O’Leary would have traveled in a sickly state. It would have made more sense if he had been left behind at the military hospital at Ft. Douglas rather than make the journey at all. There is nothing in the records about this. We do know that measles and tuberculosis outbreaks were common among military units throughout the west at this time. Neither Ft. Douglas nor Ft. Wingate would have been spared such occurrences. Perhaps he was ill yet undiagnosed.

Fort Wingate, New Mexico

Originally the site of Fort Fauntleroy (est. 1860), Fort Wingate was created after the former was abandoned during the US Civil War as troops were needed elsewhere. Following the end of that war, and in order to maintain a police force to monitor the Navajos and defend against the Apaches—primarily to protect the construction of the Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe Railroad—a new outpost was created.

By the turn of the century, the return of the Navajos to their ancestral lands following the failed fiasco that began with the Long Walk had created a peace of sorts at the Fort and nearby Gallup, 12 miles to the west. Barring the occasional Apache raid, the soldiers at Fort Wingate had to deal with mostly “nuisance issues” among the Indans. For this reason it had a rather sparse staff.

The “nuisance” Indian issues dealt with at Ft. Wingate

[The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 25 April 1901, p. 17]

this post is a S.O.B. and no question – tumbled down, old quarters, though Stots [First Lt. John Stotsenberg] is repairing it as fast as he can. The winters are severe… it is always bleak and the surrounding country is barren absolutely.

In early 1900 a fire broke out in one of the mens barracks that decimated the quarters. Personal belongings and official records were destroyed as well. This all added to the hardship of the men who were stationed there.

The boredom must have been intense and sickness surely took its toll. There were all of some 58 men at the fort in early 1901 when 2nd Lieutenant Charles L. Woodhouse arrived with the 65 men of the 23rd Infantry.

Officially decommissioned in 1912, the former fort served as an internment camp for just over 4,000 Mexican Federalist troops and families fleeing Pancho Villa’s uprising during 1914-1915; it then became an Indian school in 1925; and during WWII it was the training facility for the Navajo code talkers.

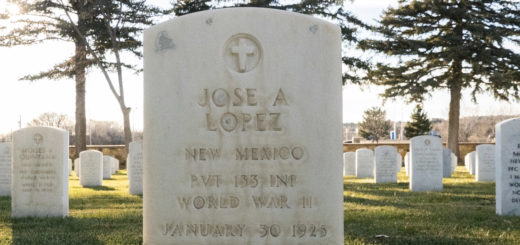

The graves of the Fort Wingate soldiers and civilian workers—including many Navajo scouts—were moved to the Santa Fe National Cemetery in 1915, though a few graves of some Navajo and Mexican refugees remained (some Navajo veterans are still buried in the old cemetery today). Pvt. O’Leary’s remains and tombstone were relocated as well.

Since many of the old Fort Wingate records were destroyed, we’ll never know precisely who Private Dennis O’Leary was nor what he was doing up to his final days but at least we now have some idea of the conditions under which he endured. I can only conclude that he lived a life that warranted someone to honor him in this manner and he continues to be honored in the Santa Fe National Cemetery to this day, Section A2, Site 956.

Recent Comments