Early 20th Century Autocamping

The rise of the automobile in the very early part of the 20th century created a unique cultural movement that lasted for some 25 odd years. In 1910 there were approximately 460,000 automobiles in the United States1. As mass production lowered costs and increased availability, the automobile was adopted more and more by a growing middle class, all because of Henry Ford’s dream. By 1925, a dozen years after the first cars started rolling off his assembly line, there were 17.5 million registered automobiles on US streets and roads.

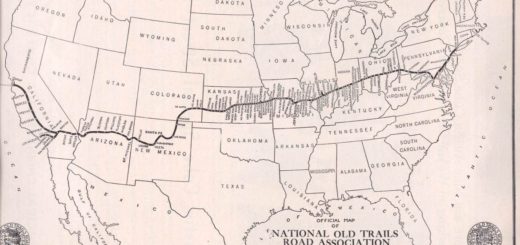

At first the automobile was seen as an easier, more convenient means to move about cities and towns. Travel between towns was a different matter and required more traditional modes of transportation such as wagons and trains. This, too, changed relatively quickly as standardized parts became readily available for the all-too-adventurous motorist who suffered the occasional blown tire or broken axle when taking his car outside the city and onto old wagon trails and even less developed routes into the countryside.

Day trips outside of the city become more and more popular as part of weekend leisure activities. Day trips turned into overnights and eventually into lengthier, multiple day excursions. This was some 20-30 years before the rise of motels. Everything that a group of motor-tourists would need on the road would have to be taken with them, from mechanical parts and tools, to tents and other camping gear. The era of autocamping thus began.

A unique culture around this means of travel sprung forth as well. The seeds were sewn by the wanderlust created by the previous century’s Romantic writers such as Thoreau and Whitman. Vestiges of 19th century American Bohemianism lent this culture its ideals and vocabulary while itself was becoming transformed into the later artistic and intellectual movement.

By and large the people engaged in the newly rising pastime of autocamping eschewed more traditional and bourgeois means of leisure travel. They traded in fancy dress at upscale hotels for rugged work clothes and bare minimum sleeping conditions. They referred to themselves – and frequently by writers of the day – as gypsies, vagabonds, and tramps. Autocamping became synonymous with hoboing or vagabondibng.

As with any such cultural coopting, there were limits to how much would be embraced. As established autocamp sites sprang up in towns anxious to welcome tourists and the money they spent, a division occurred between the well-to-do traveler of leisure and the true downtrodden tramp looking for a free stay. It was one thing to emulate the idyllic, carefree life of the fellow setting off to explore the world in a devil-may-care attitude, but it was an entirely different and loathsome thing to actually be that fellow.

It is with this in mind that I present the following piece. It is a first-hand account of a two week autocamping excursion taken by a writer for the New York Times and a group of convivial mates. It was published in the Sunday edition of the Times on July 30th, 1922, page 101. (Full text below image.)

Two Weeks' Vagabonds

TWO WEEKS' VAGABONDS

New England Roads Filled With Vacation Wanderers on a Foot-Loose Holiday

By COREY FORD.

We had it out over our pipes, four of us around a table one hot night, and we decided we'd do it. And so we did it, and had two weeks of it through the White Mountains and Canada, and it cost us apiece $21.26. I remember how that fact particularly impressed Mac, the Scot.

The engineer thought it couldn't be done the way we had planned, but he was willing to lend his car for us to try it. The Scot said that he'd come with us provided we promised to cook our own meals and live as cheaply as we could. The steward and I were filled with the idea, and swore that it was the simplest thing in the world, even if nobody had ever thought of it before. And so we did it.

As a matter of fact, we found that it was not the newest thing under the sun. There is a great camaraderie of the open road between those who have learned how to do it, which has spread all over New England. With no great to-do and no fraternity emblem save a healthy tan and a smile of good humor, the clan is growing rapidly. The roads of New England are filled with cars carrying two, three or four persons, wearing army shirts and Boy Scout knives, with blankets behind and the road ahead. They have no particular destination in mind; as frequently as not their nondescript Pegasi will approach from opposite directions and pass with a blurred hail of greeting. Although their destinations are manifold, their aim is one: the fascination of endless wandering, like the snail, with their houses about them, over the roads in the wonderland of the White Mountains.

The cracker-box jury on the porch of the country store has recognized them; and its recognition is not a thing to be dismissed lightly. For a couple of years this jury has sat on the front porch of the village Post Office and country store, as these cars have drawn up before it, and the steward of the trip in his khaki has attacked the food counters to stock the camp larder for the evening meal. The cracker-box jury sits in solemn conclave; one in a G.A.R. hat munches a reflective pipe and then speaks, "Well, El, see them campers is comin' again this year," he observes. Thus the new Thoreau are recognized; they are now an Institution.

There is nothing easier to arrange than this trip up Parnassus. Some one of your friends must have the car and the time to steal away with you; a little Ford station wagon is chariot sufficient, a small box-kite affair erected on a truck platform, with brown side curtains that you may roll down for necessity or for modesty as the case may be, and seats that may be removed or shifted at will. In the rear you stow the four suitcases—there are four of you going—two or three blankets apiece, tin cup and plate, knife, fork and spoon, several indiscriminate pans that you have salvaged from the kitchen, and—happy thought—an iron grate which you removed from a convenient coal stove in the unguarded flurry of departure. And $21.26—though perhaps you had better take around $22, in case you wanted to spend a little extra. And yours the hill and valley, the open road.

Now is the time for all good men to spend two weeks in the country, each one with three friends who are congenial and tired, only making sure that one of them has a car that isn't too new, then set out upon the open road. The ways and byways of New England are full of them—college men who won't start work for two weeks, and business men who have stopped work for two weeks.

Climbing Parnassus.

It is the ideal existence, to loaf along thus with luggage in the back of the car and no particular place in view, although if you're of that turn of mind and must have one, there's always Canada. No seashore resort or mountain hold gives you that sense of detachment and complete rest. You are your master, the road is ahead; you eat as you please, cooking your meals over an open fire; sleeping when you will under the stars, waking with the dawn; swim in a mountain lake when you will, catch fish in a mountain stream when you will, or when they will; and always the road ahead. Thoreau at 29 cents a gallon.

Lunch is a brief halt under a shady tree, where a near-by brook rattles away over pebbles. A loaf of bread, a slice of ham and a cup of milk is your Rubaiyat, which you have purchased in a village store. A rest, then on through the afternoon.

Come 6:30 in the evening—or, if the daylight saving time is confusing, as your appetite dictates—and you stop at a country store for the evening meal. The steward has ruled steaks the order of the night, and beans and corn, potatoes, bread and cake complete the board, with milk from Farmer Brown's up the road a piece. Then on into the untrammeled country, till the last farmhouse is left miles away and the hills are the forest primeval. A break in the laurel growth at the roadside is barred by a couple of birch logs, and a suspicion of an overgrown road leading up a hill of arbor vitae and laurel suggests the cleared space of a deserted lumber camp at the top. The scouts report favorable conditions, the bars are lowered, and the motor car toils up the rocky path to the desired spot you expected. The car is halted on the knoll, the steward is already busy with a pile of gray rocks near by, and in a jiffy they are molded into a fireplace, with the grate perched precariously atop. While the Scot unloads the car and bemoans the loss of his toothbrush, and Scribus and the engineer set out the plates and utensils on two convenient stumps lopped at table height, the steward soon has supper sending forth lingering aromas over a fire whose blue smudge of smoke makes sport to hasten the gathering haze.

You smoke a lazy pipe by the coals when the evening meal is over and the dishes scoured with roots and dirt and put away. The steward has a mandolin; there are songs which belong to the firelight, and you sing them all in impromptu quartet. College songs, negro songs: "Dese bones g'wine rise again!"; odd songs. One by one you drop out of the quartet, till the mandolin carries the refrain alone, and you look up at the stars. And presently you spread the poncho and raincoats on the ground, and roll in blankets upon them, and with the imprecations of the Scot in your ear, as he removes sharp rocks from the small of his back, you drop off to sleep the sleep of the out-of-doors until dawn arrives and breakfast, and you are on your way again.

The beaten trails, of course, out of New York. The Boston Post Road will lead you a delightful route around the serene coast of aristocratic New England. Through New Haven, whose folk will hasten to assure you that they have something else there besides a college; through Bridgeport, where you get a puncture; on, out, along the coast to tidy little Rhode Island, who sweeps her front lawn with a broom and whitewashes her fences. On to cultured Massachusetts, who leans backward to remember her history and where dates, not street numbers, identify her dwellings—"Salem, 1592," you say, or "Concord, 1776." Then to Lexington and Concord, the Revolutionary pair, and discover there that Paul Revere did not complete his Midnight Ride; that the Rude Bridge no longer arches the flood, but is replaced by a thing of concrete; and that visitors are not admitted to "The Old Manse."

Riding Through the Past.

Pause for a moment outside "The Old Manse," the more impressive because it is not heralded by a date nor explained by a tablet. You recognize it from photographs you have seen, a gray building of simplest design standing aloof amid its sentinel of trees in dignity there; picture if you will the silent man who would walk its floors, "a little knot gathered in his forehead that always appeared when he was deeply thinking," as Brander Matthews used to describe him at Columbia. Back over the medieval cobbles of Boston, out to Salem, with its shining new brick walls testimony to its recent disaster of fire; and count all Seven of the Gables at Hawthorne's house, and observe the beaten path in the living room that leads to the chair where every sightseer has sat since Hawthorne. Until at length the hills commence to roll, and the clouds to build into ponderous white masses, and you are up the coast and into New Hampshire.

There are infinite trips to take in the wonderland of the White Mountains; but if you are of the initiate you will let yourself go, and stumble on these by chance. You may come upon Hanover, and be the royal guest of the cordial collegians in their beautiful surroundings there. You may roller-coast through the primeval shadows of Bretton Woods. Or, all by chance—if you have ignored the signs—you may approach the Old Man of the Mountains, and in his face, made familiar to you and granted power of speech by Hawthorne's tale, you will read the solemnity of the mountains. The Scot took a picture of it with his camera, which he said was every bit as good as those expensive cards they were selling. The engineer explained to the steward how a country clergyman, a few years ago, had scaled the mountainside, and from a precarious height had secured the slipping forehead with iron staples. Scribus looked at it a long while without a word.

You may climb a mountain and find you are at "Lost River." You stop; it is pouring rain, but that doesn't bother you. Many years before—you learn parrotwise from the guide—a mountain torrent had eaten a canyon down the slope of rock; earthquake, or glacier, had shattered the tops of these canyon walls and brought them tumbling about its ears. So with guide, overalls and candle you lower yourself in the rain down wooden ladders into crazy caves and holes of monstrous shape and imaginative name, where a cataract booms the foot. In impossible blackness you worm feet first through holes twice your length into a hollow cave at the end, where water churns yellow around a single boulder which your feet must find, and upon which you crouch and listen to the boom in your ears like the pounding of the engines on great ocean liners. There are caves atop one another, hour-glass fashion, and you lower yourself down apertures in the floor of each, with the gray-rain sky rapidly growing more indistinct overhead, through the earth to a lost river that flows through the centre of a mountain.

The guide is a young college man, and he recites geological explanations of the phenomena before your eyes with all the monotonous precision of a college lecture. But when the rest of the party have their backs turned he responds to a gleam of amusement in your eye with a similar flicker in his own, and doffs his dignity for a space. He recounts with good fun the reactions of the usual sightseer to these glories of nature. "Yes, that's a very nice waterfall, isn't it? My, you don't have to go to Niagara!" or "Think of all the water power going to waste there!" He has just taken the job for the Summer; you envy him this opportunity to study first hand the constant supremacy of little minds over big matter.

Could there be a more satisfactory existence than this one of freedom and rest? Where the roads lead you follow; if you will, you stop by a mountain lake where shore is lined with the skeleton-white branches of dead trees which the newer growth has pushed out into the water, and in that icy water and hot midday sun you bathe. Where a pine forest marches like an army up a gentle hillside you camp for the night, spreading your blankets with the reckless luxury of a plutocrat upon a bed of pink lady's slippers, or sinking inches deep into a mat of moss that has formed there for centuries. The wind is in the pines; and not very many mosquitos.

So when we returned home we had it to over our pipes again and decided it was the ideal vacation and we would do it again and again. As long as the Ford held together, said the engineer. And the Scot figured that next time we could do it even cheaper than $21.26.

- United States Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration statistics.

http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ohim/summary95/mv200.pdf ↩

Recent Comments